Introduction

This essay is an argument against fetishising power, in favour of a grounded and revolutionary optimism. I offer a critique of pessimistic attitudes, an overview of the material factors contributing to the collapse of the U.S empire, and an explanation of how the People’s Republic of China is undermining the structure of imperialism. For those who want to just hear my main arguments, I would recommend reading Part 1 and the conclusion, even if the essay works best as a whole. The amount of evidence and quotes I have provided may prove exhausting in one sitting; I probably could have used an editor. Despite the length, justifications cannot be provided for every single claim: some earlier drafts of this essay dived into tangential points, where due to their controversy, there was a certain self-consciousness about proving their truth to the reader. I would love to assuage any and all doubts, but this essay is already 15,000 words long – brevity is a quality I (try) to strive for. For readers that profess scepticism in anything I say, or just want to learn more, there will be book recommendations at key points, as well as a wealth of footnotes.

With that said, I hope you enjoy this piece. Feel free to leave a comment with thoughts, constructive criticisms or counter-arguments; I welcome any feedback and would be happy to discuss. I will be trying to get something uploaded to REPORT OF ANIMALS every couple of months, so stay tuned for more.

The Demiurge Does Not Exist:

or the Problem with Pessimism

- Introduction

- The Demiurge Does Not Exist:

- or the Problem with Pessimism

- Part 1: An Immutable Shadow

- Fetishising Power

- The Demiurge & Revolutionary Pessimism

- Part 2: This Too Shall Pass

- Necessary Meddling and the Delay of Decay

- The Core Breakdown

- The Imperialist World-System

- The Peripheral Position of Russia and China

- Part 3: Hope Built on Certainty

- The Imperialist Breakdown

- China’s Efforts to Combat Underdevelopment

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

Part 1: An Immutable Shadow

Fetishising Power

Despair is typical of those who do not understand the causes of evil, see no way out, and are incapable of struggle.

– V.I. Lenin1

A major interest of mine for the last two years has been “parapolitics”, or “deep politics”: as defined by scholar Peter Dale Scott, it is the study of “decision-making and enforcement procedures, outside as well as inside, those sanctioned by law and society. What makes these supplementary procedures ‘deep’ is the fact that they are covert or suppressed, outside public awareness as well as outside sanctioned political processes.”2

In essence, it is conspiracy theory with a materialist lens – real world conspiracies are simply collusions between members of the ruling class, that implement plans to forward their interests. Although parapolitics distinguishes itself from the popular conception of “conspiracy theory” by using historical evidence and grounded analysis, this does not necessitate a deflationary attitude – sometimes covert actions by the powerful are indeed grand, outlandish and evil. Vast networks of drug and human trafficking, sexual blackmail schemes on billionaire islands and NATO-organised Nazi terror attacks are just a few examples of these historical realities.

My thought has shifted since delving into parapolitics, and I have some conclusions on its utility. I recently watched Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Industry3, an exposé on the control the arms industry has over politicians and their decisions to go to war. It is a well-edited, engaging piece of work, and one I would show to someone as a great introduction to the “deep” aspect of politics. As excellent as it is, I did come away from it wanting more; for as much as it exposes the sheer scale of corruption and profit behind war, it seldom shows the cracks in the hegemony it depicts, or lends the countervailing forces of resistance as having any kind of hope. While I am glad it treats the subject with the seriousness that it deserves, and does not try to placate the viewer with promises of mere reform, the documentary leaves the viewer with the feeling that war is eternal.

This is a frequent problem in political media, or media in general: simply depicting a problem is not enough. Portraying or pointing to the inequalities and abuses of capitalism has to come with the practical solutions to these problems, otherwise it is an exercise in despair – an informed despair, yet despair nonetheless. This is critique as exposure, shining a light on the problems as opposed to demonstrating the fallibility of these problems. Something missing from documentaries and books like Shadow World is the premise that despite the overwhelming power of the U.S Empire, it is inevitable that it will fall. The brilliance of a work like Marx’s Capital is that it demonstrates the sheer power of capitalism, its ability to extract immense quantities of wealth and social control, while simultaneously showing the power of labour, the protagonist who will break its chains and bring in the next necessary stage in human development. In Sobrina de Alguien’s essay The Narrative Devices of Criticism: Capital vs. Breaking Bad4, techniques of narrative construction are analysed to show how mere depiction of a problem such as “sexism” or “greed” are not the same as a proper critique of a problem; two techniques particularly relevant here are that of “Historicization and Fetishization”:

Historicization shows that all things have an explanation, a beginning and an end, whereas fetishization presents them as opaque and eternal. In other words, historicization is a kind of centering that is a partisan of intelligibility and change, whereas fetishization invisibilizes both. For those who understand historicization as the defining aspect of critique, to criticize is to make understandable both the spatial-temporal limits of a thing and the laws of its movement, with the ulterior motive of directing its transformation towards a desired end.

While Shadow World differs from media like Breaking Bad in that it does not strictly “glorify” the arms industry as such, it does not offer anything other than representation of the problem. Its strength lies in the fact that it offers a materialist analysis of why wars occur, of how economic motives drive conflicts, but its weakness is that it presents this as an intractable problem. One of the key insights of dialectical materialism is that things are not stable forever, an entity is always “coming to be” and “passing away”, and this process of internal inconsistency ensures that nothing is eternal and change is inevitable; it is cliche to say that “Empires rise and Empires fall”, but this never seems to apply to our own situation. The lack of a hopeful message is understandable: in trying to apprehend imperialism and mechanisms of control, a primary task becomes learning the tools the United States has used to bend the world to its will, a seemingly endless topic. The sheer number of interventions and “deep events” the CIA has been involved in almost beggars belief, and the picture of an overwhelming, insurmountable power becomes ever-stronger the more one explores the historical evidence. One quote uttered by an arms-dealer in the documentary, “Lockheed Martin makes the Mafia look like schoolboys”, is a succinct way of describing this scale one is confronted by. For the aim of the documentary, it does make sense to only reference revolutionary situations in the context of their suppression, but the sole solution offered by the documentary when faced with this suppression, is a hypothetical gesture towards “a system based on love”.5 To reinforce this notion, the documentary ends with images of Red Army soldiers reuniting, hugging and throwing their hats in the air. While comforting, there is a difference between this naive optimism and the concrete optimism I advocate; we should have more than the simple ability to posit a better world, we need to scientifically prove that the better world is both possible and necessary.

The crucial aspect this documentary is missing is dialectical thought. This sounds like a Marxist cliche, but let me explain: while the documentary describes the military-industrial complex, nothing is offered in describing the internal antagonisms of the system that will lead to its dissolution. The reality is that the very wars that perpetuate destruction and underdevelopment for short-term profit, create long-term conditions for an informed resistance; nobody can say that Libya’s destruction at the hands of NATO has created fertile revolutionary soil in the country itself, but it has demonstrated for other countries in the Global South that if you seek a different development path other than austerity and underdevelopment, you cannot trust the Western financial system to not turn to war. This has led cooperation by these countries in the face of this threat: the recent success of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation Summit (FOCAC) is explicitly aimed at mending the “historical injustice” dealt by the West, with African leaders extolling China’s role in “combating colonialism”.6 We can see that learning from experience is difficult, but it is the only way that change occurs; every terrible action by imperialism has its opposite reaction, and the historical experience only strengthens the appeal of countries like China that offer an alternative path. Imperialism’s self-interest, a system based on creating instability, cannot create a stable situation for its self-perpetuation.

In this way, Walter’s process of change is itself fetishized. Though it is explainable and situated in time, it isn’t avoidable. Moreover, Walter never understands the laws of his own development. He’s passive and blind with respect to his own motives. He’s eternally condemned to a process of change that he can’t understand or control. Whereas in Marx the project of observing the enemy is subordinated to the goal of defeating him, in Breaking Bad observing Walter’s transformation is an end in itself. It’s not about empowering the audience to fight this villain, it’s about getting to know him as a person so that we can, in the final analysis, accept him.

The Demiurge & Revolutionary Pessimism

In Gnostic religion, the creator of our earthly existence is in fact not God, but rather the “Demiurge”; a lesser deity that created the material world we are trapped in, a fallen image of the ideal divine world. Rather than accepting existence for what it is, and seeking to change it, the Gnostic consigns themselves to escaping this metaphysical “black-iron prison” through inner salvation of the mind; any worldly attempts to evade the Demiurge’s torments are thus pointless, and its evil is responsible for all our suffering.7

Thus we come to the meaning of the title of this essay, where some fetishise the power of capitalism as an inescapable, all-controlling Demiurge.

Those that lack Marxist analysis will often view the scale of the CIA and U.S military’s power and fall into nihilistic despair. From this vantage point of endless horror, the system seems immense and unsolvable, with revolutions impossible despite historical evidence to the contrary. This nihilism and fetishisation of power flattens different wielders of power as having the same self-interested goals, or sees the system of power as controlling every actor on the global stage; this is what leads some to conflate “Soviet power, Marxist ideology or radical Islamic fundamentalism” as having the same “profoundly undemocratic” mechanisms.8 This reduction of difference can lead some to see their power as “just-as-bad” as any other, justifying imperialism as one kind among many, or it can lead to a complete disavowal of power; this tendency, born from the tragedy of the world, is typified in the anarchist. While the intentions for a better world are present, the focus on horizontal purity leads to an uncompromising view of politics that excludes most anti-colonial projects as corrupted by hierarchy. Viewing power as corrupting any and all who have it, ends in conflating the very real differences between these groups; socialist states such as the USSR and the PRC were created in anti-colonial revolutions, called repeatedly for oppressed peoples to break their chains, while being surrounded by imperialist encirclement. Equating these uses of power, a defence posture born of a state of exception, with the actions of settler-colonial nations, belies a lack of historical analysis.

Conflation between uses of power means historians who engage with the crimes of U.S empire can inexplicably return to a naive liberalism, unable to properly analyse the primary motive of private profit and settler-colonialism; Peter Dale Scott, the scholar of deep politics mentioned previously, falls into this category. Rather than seeing their victories, Scott sees revolutions as a “lobotomizing of society”, and tars all the historical instances of Marxist revolutions as “disasters”, with the curious exceptions of China and Vietnam. An advocate of “preserv[ing] the American Republic”, Scott sees “a soft politics of nonviolent persuasion” as the strategy for changing “institutions that, although worthy of preservation and respect, are clearly not working as intended.”9 This begs the question of what the actually-existing intentions of these institutions are, and whether they were indeed created with democracy in mind. Stafford Beer’s heuristic, “the purpose of a system is what it does”, seems particularly relevant here: there is “no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do.”10 Rather than reconsidering the basis of the American project itself, a nation founded by slave-owners and on the extermination of indigenous peoples, Scott prefers to hope for the powers-that-be to allow for reformist change.

Elsewhere, in philosophical circles, the logic of capitalism itself is fetishised as a demiurgic force that cannot be stopped; this either expresses itself in a depressive pessimism or a fascistic enjoyment. Putting aside the priests of capitalism who insist like Margaret Thatcher that “There Is No Alternative”, a feeling of pessimism and scepticism is a recurrent theme in many writers who are ostensibly “Marxists.” Domenico Losurdo’s Western Marxism deconstructs this tendency in figures such as Foucault and Adorno with great eloquence, so I will limit myself to a handful of more contemporary philosophers that exemplify this trend.

Mark Fisher, icon of the British academic left, is best known for his critique of capitalism’s stultifying effect on culture and his analysis of “capitalist realism”: the inability for society to imagine anything beyond the current system. It would seem at first glance that his project is relevant, as he seeks to do away with the ideology that capitalism is eternal and undo neoliberal fetishisation. However, as much as he complains about ideological boundaries and advocates for radical thinking beyond it, he cannot think outside the white picket fences of the Western world – there is a severe lack of attention for the question of imperialism, and therefore, he finds there is not a single socialist state he can support.

To his credit, as discussed in the essay “how to kill a zombie: strategising the end of neoliberalism”11, Fisher rejects anarchism and avoidance of state power. Unfortunately, the problem with his outlook lies with the outright dismissal of “old-school Leninism”, while presenting no real organisational alternative other than a reference to “Hegelian plasticity”12. His caricature of the “Harsh Leninist Superego” exposes the vacuousness of his thought: Fisher characterises this tendency as “stak[ing] everything” on a world absolutely different to this one”, which results in “an indifference towards current suffering” where we “must step over homeless people, because giving to charity only obstructs the coming of the revolution”13. This phantom he conjures has no real bearing on actual Marxist-Leninists, many of whom engage in mutual aid and argue for the construction of socialism out of the current conditions of material reality. In actual fact, it is Fisher who presents a world “absolutely different to this one”: the closest he came to a positive project in his career is the hazy notion of “Acid Communism”, in which he places vague hope in utopian “group consciousness” and the latent promise of the song “Psychedelic Shack” by the Temptations.14 As someone who has enjoyed psychedelic experiences and elements of the counterculture, I can also recognise that they are not conducive to effective political action; as documented in the book Drugs as Weapons Against Us15, acid and other drugs have been used to hinder the anti-war movement and ruin the lives of activists. Fisher sees drugs as “affect[ing] time perception”, which means “you are not prey to the urgencies which make so much of workaday life a drudge”16; this theme of anti-work runs throughout his writing, but there is seldom thought for the work required to build socialism, nor the work done in the Global South that fuelled the welfare state he is nostalgic for.

Fisher sees 1973’s Western-backed military coup against Salvador Allende as the disappearance of a lost world, a part of neoliberalism’s war against “the various strains of democratic socialism and libertarian communism that bubbled up in so many places […]”17. Allende’s Chile is seen as a special case of Marxist government, a “democratically elected, non-authoritarian, technologically-orientated administration”18 that ended in tragedy. Here I fail to see how this description of Chile is fundamentally different than “the necrotic Stalinist monolith of the USSR”19 that Fisher denigrates, other than how Chile was crushed before it had the chance to alienate Western academics; the USSR was a country born of people’s revolution, that set to work industrialising and reducing poverty for all its citizens, while beset by one of the largest colonial counter-revolutions in history and one that destroyed the Nazi effort to construct a “German Indies”20. What Fisher omits is that Marxism in Chile failed precisely because of its avoidance of Lenin’s teachings about the threat of imperialism and Allende’s lagging commitment to the bourgeois electoral constitution, with Fidel Castro warning the Chilean leader to take control of his military lest the imperialists attack, an event that subsequently occurred.21 While Stalin occupies the role of demagogue in the Western imagination, the truth is that he was elected to the role of General Secretary against his wishes22, and managed to maintain socialist construction amidst a thirty-year internal war that sought to sabotage the October revolution. This is not to say that Stalin was perfect, far from it, but the USSR’s political system was not the work of a single all-powerful man (as CIA documents attest23); he was a committed communist who continued Lenin’s legacy, and one that was mindful of the question of imperialism:

Formerly, the national question was usually confined to a narrow circle of questions, concerning, primarily, “civilised” nationalities. The Irish, the Hungarians, the Poles, the Finns, the Serbs and several other European nationalities[…] The scores and hundreds of millions of Asiatic and African peoples who are suffering national oppression in its most savage and cruel form usually remained outside of their field of vision. They hesitated to put white and black, “civilised” and “uncivilised” on the same plane. […] Leninism laid bare this crying incongruity, broke down the wall between whites and blacks, between Europeans and Asiatics, between the “civilised “ and “uncivilised” slaves of imperialism, and thus linked the national question with the question of the colonies. The national question was thereby transformed from a particular and internal state problem into a general and international problem, into a world problem of emancipating the oppressed peoples in the dependent countries and colonies from the yoke of imperialism.”

– Joseph Stalin24

Though often a term used by defenders of socialist construction, Fisher discusses the “purity fetish”25, the idea that we should not prioritise ideological perfection in spite of material good. This is in accordance with Lenin, who likened a successful revolution to climbing a mountain, where you cannot just leap to the summit – there are moments you must go down in the short-term, to proceed in the long-term. Contradictions due to incessant imperialist pressure, difficulties in organising production and the legacies of bourgeois society will always arise; this doesn’t mean criticism towards decisions is outlawed, but there is a difference between constructive critiques in the face of adversity and complete disavowal in the name of ideological purity. However, Fisher directs criticism of the purity fetish towards those who criticise social-democratic parties like Podemos in Spain and Syrzia in Greece, non-revolutionary organisations enmeshed in the Western electoral system that have widely failed, rather than actual socialist states in the Global South that have to act against imperialist pressure.

In light of this, Fisher’s warnings of engaging in “authoritarian-nostalgic Leninism”26 are strange, considering the success of Leninism in the Third World, with many national liberation struggles being inspired by the Bolshevik, Chinese, Vietnamese and Korean world-historical overthrows of the colonial yoke. Organising techniques of Lenin such as democratic centralism and vanguardism are still used throughout the Global South, in Nicaragua, India, Kenya, Cambodia and South Africa, to name a few. Lenin’s clarity in describing the global class struggle, in showing how “workers of the oppressor nations are partners of their own bourgeoise in plundering the workers (and the mass of the population) of the oppressed nations”27, is completely disregarded. Fisher’s nihilism for the possibility of socialism even manages to equate the Bolshevik’s attempt to change their country’s culture for the better, with that of neoliberalism’s use of think-tanks28, flattening both into the murky category of “authoritarianism” and “market Stalinism”29. What Fisher fails to cognisize is that the class struggle is no longer a simple relation between bourgeois and proletariat isolated to each country; it is the global struggle between imperialist nations and oppressed nations that conditions the field of action.

The philosophical project Fisher claimed to pursue, an undoing of entrenched capitalist ideology, only resulted in musings on cultural stagnation and depression; he is bewildered by the lack of a strong workers movement in the imperial core, yet he ignores their material comforts gained from super-profits and the actually-existing anti-colonial struggles around the world. Here we can see how Fisher is a perfect example of “contrast[ing] the poetry of the remote future to the prospect of the long-term prose of immediate tasks”30, happy to criticise the decisions made by those who have taken power, while positing an imaginary movement so far from any concrete anti-imperialism, that it is no surprise it has failed to gain any traction.

Thus, despite his insistence on an alternative, he dismisses all real attempts to build one.

At the extreme end of the philosophical fetishists of capitalism are the accelerationists, who essentialise the logic of capitalism as intrinsic to the world itself. They do not believe that it is historically necessary or possible for a new system to emerge, and instead advocate for a strategy of pushing capitalism’s exploitation further, giving it more and more power in a nihilistic manner until it either creates a dystopia run by A.I (in Nick Land’s view) or creates the small possibility that it collapses under its own contradictions (as tentatively postulated by the French post-structuralist Gilles Deleuze). While capital does act as an automatic logic controlling workers and capitalists alike, an “inhuman power”31 as Marx puts it, it is not invincible; the fetishistic view ignores how internal contradictions within the logic of capitalism, where capital becomes a barrier to itself, cannot help but create external antagonisms that outcompete it. In fact, there are very real threats towards its existence that are currently playing out in the real world, that rest on an active opposition to imperialism’s goals rather than a reinforcement of said goals.

We can see all these writers share a common problem.

Pessimism, or scepticism, is not directed towards reforming capitalism; rather, they are pessimistic about the possibility of revolution and the building of socialism.

This pessimism is destined to wither. The dark mood emerging since the fall of the Soviet Union, the proclamation of the “End of History” and the failure of the Occupy movement, is coming to an end; since roughly 2020, the decline of the United States as global hegemon and the obviousness of its internal and external antagonisms has created a new influx of class consciousness. The process is by no means complete, with many still holding pessimistic attitudes about the omniscience of capitalism – but I contend that the historical forces that should generate optimism are only increasing. The genocide in Palestine, the climate crisis and potential for all-out war with Russia and China are ominous clouds hanging over the world, but these are symptoms of a much larger historical process that should be cause for hope: the collapse of the American epoch. I hope that this next part serves to let a little light back into the room; this is not a complete guide to Marxist insights, but a pointer towards trends that combat a fetishistic pessimism.

Part 2: This Too Shall Pass

Necessary Meddling and the Delay of Decay

It is not always the majestic concerns of Imperial ministers which dictate the course of history.

– Frank Herbert, Children of Dune32

The scale of subterfuge engaged in by the U.S empire is to put it simply, horrifying. One can read books like William Blum’s Killing Hope, John L. Potash’s Drugs as Weapons Against Us, or C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite, and still not find a complete picture of their crimes.

However, this activity by “the forces that be” demonstrates a simple truth: active and constant effort is required to maintain the system of imperial domination and capital accumulation. The inherent forces of history do in fact tend towards liberation, and only by attacking these forces, do capitalists gain time in their pursuit of more power and wealth. This process though, cannot continue forever; a structure like imperialism is not impervious to degradation and collapse, and it is inevitable and demonstrable that this structure will come to an end. The self-confidence undermined by examining problems can only be bolstered by understanding the solutions. To do this, we need to know exactly how and why the logic of capitalism is breaking down.

Here I will give a very brief overview of “Breakdown Theory” with reference to Marxist economist Henryk Grossman, and one of his best modern proponents, Ted Reese. As much as I would like to spend more time explaining the Labour Theory of Value and its implications, that is not the point of this essay; this section just serves to prove that there are objective reasons to be optimistic. If the reader would like to get a better theoretical understanding of Marx’ theory of value, I would recommend Chapter 2 of Reese’s book The End of Capitalism: The Thought of Henryk Grossman33.

The Core Breakdown

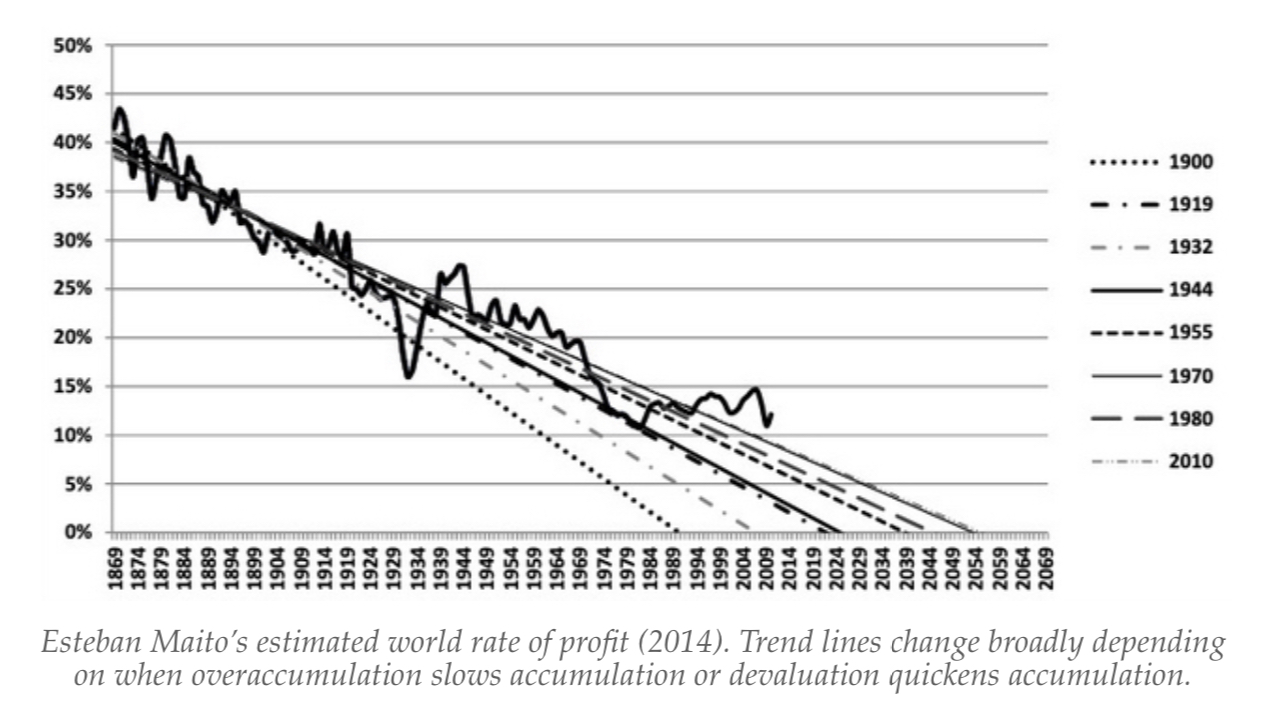

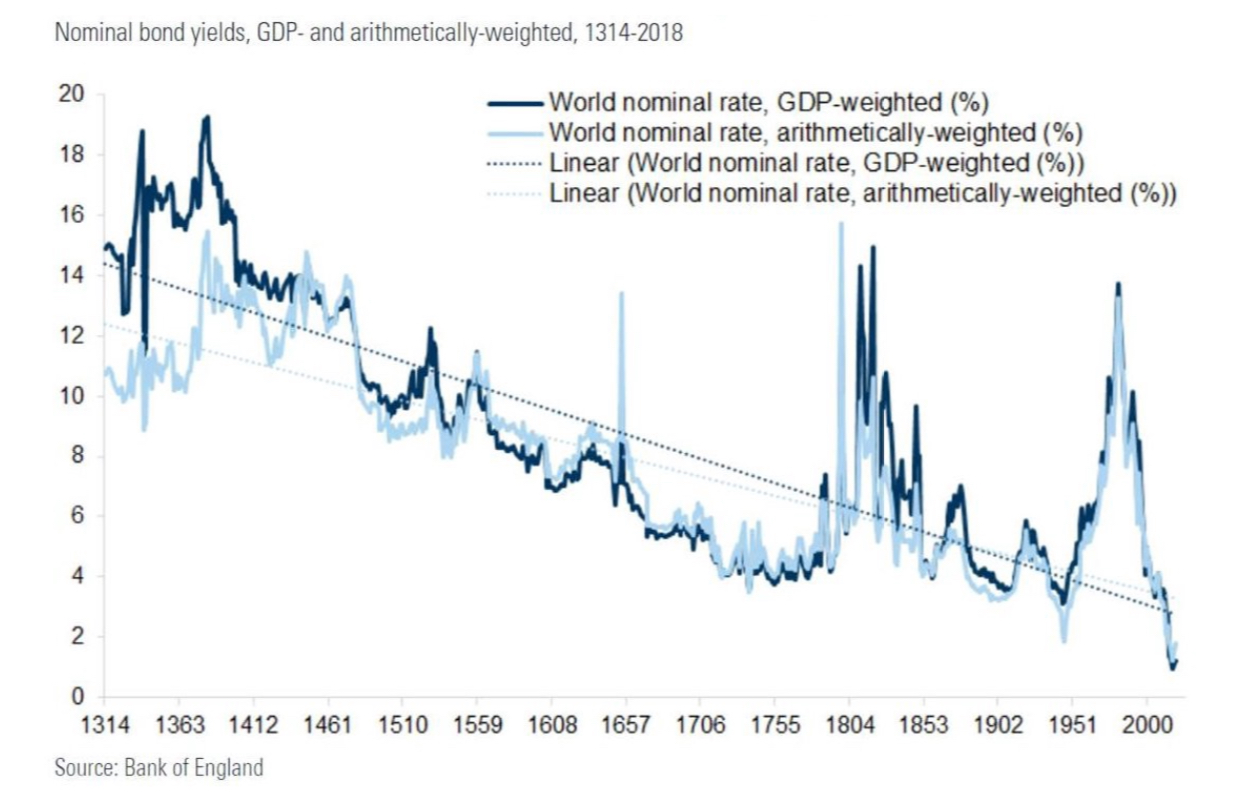

As mentioned, the dialectical materialist outlook contends that structures change over time due to the inner antagonisms that define them. This is not just a theoretical or philosophical view; we can demonstrate its scientific truth by examining tendencies in the world. Let us start with the backbone of the capitalist drive, the profit motive. Ted Reese, in his newly published work Abundant Material Wealth for All34, demonstrates with contemporary data that we are seeing increasing proof of what Marx called “in every respect the most important law of modern political economy”35: the fact that the rate of profit is progressively falling.

For a full breakdown of the breakdown tendency (ha), see Ted Reese’s works.

This is due to capitalism becoming a barrier to itself: as capitalists accumulate more and more capital (gained from exploiting the working class and their surplus labour-time, i.e surplus value), it is more difficult to reinvest this mass of capital in a profitable way – there is an overaccumulation of capital.

This is because of the antagonism between the need to increase the profit rate (amount of profit : the amount of capital already invested) and the ever-increasing costs of production; accumulating costs such as wages and equipment tend to grow faster than the growth of profits, and thus the mass of capital rises but in an ever-declining rate. Another factor inhibiting profits are the hard limits of human exploitation, as there are only 24 hours in the day to maximally utilise, so this leads to an underproduction of surplus value to extract as requirements increase. This means, in combination with an overaccumulation of capital, there is not enough labour to valorise (ability to create profit) the amount of already invested capital.

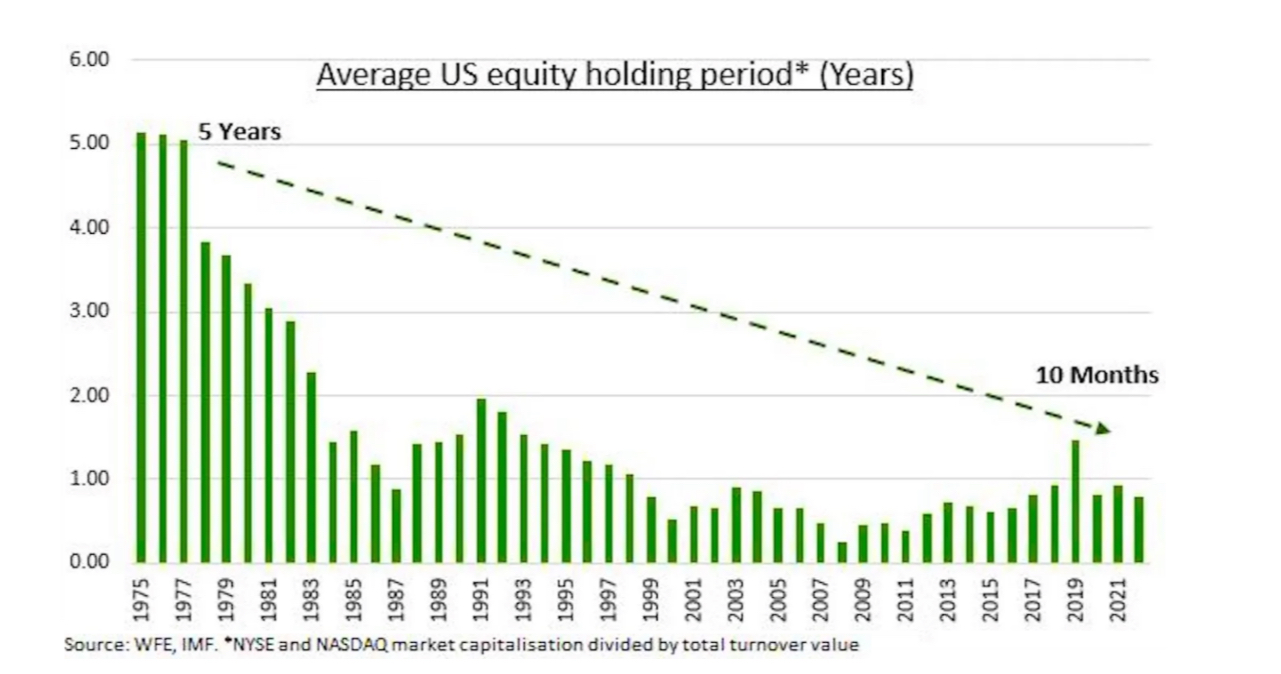

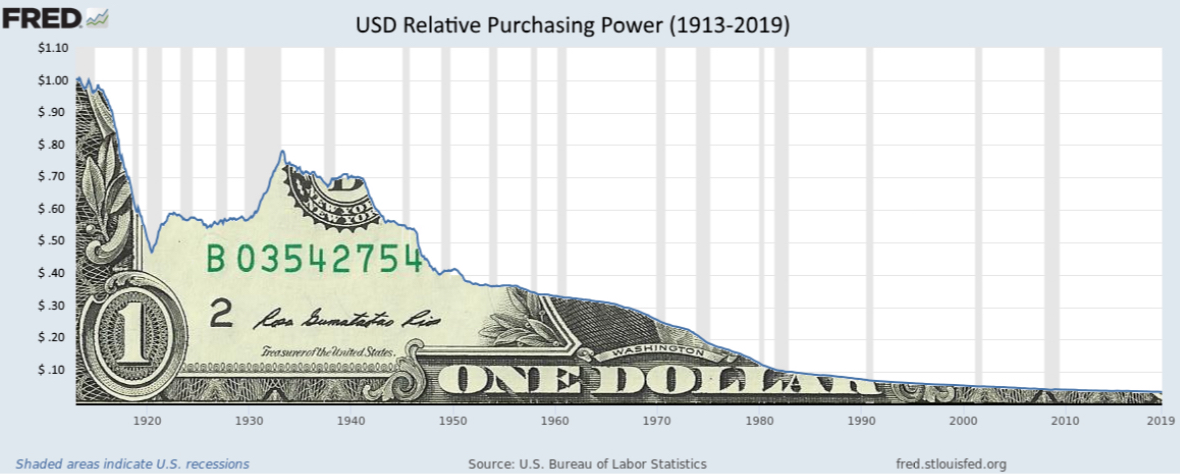

Capitalists can delay this tendency for overaccumulation through counter-tendencies that attempt to further valorise capital. When faced with fewer and fewer profitable opportunities in production, low-risk methods like savings accounts are more appealing; this leads to slow growth, which the U.S and other countries attempt to combat with low interest rates, incentivising investment into assets. These usually take the form of speculative assets such as real estate, gold, or stocks, which for profits to be made, their prices must steadily increase. This creates the infamous problem of asset-price inflation and bubbles, which inevitably pop in major crises. New technologies such as cryptocurrencies and A.I promise new growth, but they require vast amounts of capital and labour to create profit; all of these have been proven to be temporary fixes to the core problem of overaccumulation, which is exacerbated over time.

At a certain point, capital becomes pointless to reinvest, which causes businesses to shrink or go bankrupt due to profits falling, which increases unemployment. Thus the general rate of profit falls due to the failure to valorise capital across the economy, and so the whole system goes into economic crisis and recession. Counter-tendencies do arise during crises: in a recession, you get panic selling, which cheapens commodities, which also cheapens the means of production, the equipment necessary to valorise capital, and so what could not be invested before can now be invested. The economy-wide crisis of profit also compels the capitalists to attack the working class in order to recoup costs, which can be done by:

– increasing the amount of exploitation (increasing absolute surplus value),

– reducing the value of labour by cheapening commodities (increasing relative surplus value by reducing the cost of reproducing labour),

– reducing the cost of labour through increased super-exploitation (e.g domination of the Global South and depressing wages),

– redirecting surplus value from public spending to the private sector (e.g austerity, tax cuts etc)

– centralising and devaluing currency/capital into private hands, so that the value of constant capital (equipment) decreases compared to variable capital (wages).

In addition to these efforts to increase surplus value, there are many inherent drives that exacerbate the contradictions of capital in a crisis:

– Increasing competition over smaller and smaller profits results in winners and losers, mergers and bankruptcies, and thus meets its opposite: monopolisation. This leads to concentrated power and wealth, and increases the incentive to gouge customers and employees, .

– An increase in the “reserve army of labour”, i.e the unemployed. This temporarily puts downward pressure on wages, but shrinks the labour base upon which capital can be valorised.

– Innovation that causes greater productivity in less time, an example being the “just in time” system used in many places. This produces more surplus value in less time, but causes an average fall in value, in relative terms, per commodity.

– Imperialism allows for “primitive accumulation” through plunder, and for the devaluing of capital and labour-power through the destruction of war, but this era has ended, due to the instability of colonialist enterprises and the period of de-colonisation in the 20th century.

(For the sake of brevity, the rest of the counter-tendencies can be found in Chapter 2 of The End of Capitalism.36)

Counter-tendencies mean that accumulation can be restarted on a higher level after a major crisis, such as the Great Depression or the 2008 Financial Crash. This only delays the problems however, which erupt on a larger scale when the next crisis emerges; accumulation expands in proportion to the base of already accumulated capital, not profitability, meaning that the problem accelerates. Thus the valorisation of accumulated capital is becoming more and more difficult in the capitalist framework, and means that capitalism is unsustainable in the long-run. These actions taken by capitalists cannot delay the decay forever, and will necessarily end in some form of “final crisis”; rather than an eschatological prophecy, the inevitability of this event is due to the immanent processes of capitalism and their encounter with objective limits. Grossman and Reese do not advance a mechanistic, strictly economic view – the political will of the masses and revolution play a huge part in taking advantage of the crises caused by capitalism, as capitalists will not willingly relinquish power. However, as more and more structural crises strike in a quantitave manner, it will inevitably cause a qualitative change. As I will discuss, the main way this final crisis has been avoided has been the maintenance of neocolonial extraction from the Global South, a delicate situation which is rapidly eroding.

The fact that capitalism is decaying provides the motive for much of the activity that we witness in the contemporary moment. As Ted Reese notes:

Since capital accumulation is increasingly dependent on

i) mergers/monopolisation;

ii) central planning (eliminated internal

markets, centralised data, etc.)

iii) state (public) subsidies, contracts and facilities (including tax cuts);

a ‘final merger’ – a therefore public monopoly – and central planning of the economy as a whole, is becoming, for the first time, an economic necessity.

[…] Given that evolutionary phases are relatively gradual and cannot be ‘leapt’ over, the evolution of the productive forces – man and technology – now demands that ‘state monopoly capitalism’ is transcended by ‘state monopoly socialism’37

This brings us to a crucial point if we are to have hope for the future: the necessity of China’s economic system in birthing a new mode of production. Here I differ slightly with Ted Reese, who is more sceptical of China’s role in the world-system; Reese is wary of the country turning to imperialism as it rises up the value-chain of development, whereas I (and many others) view it as undermining the very structure that imperialism is predicated on. That is why before we examine China’s progressive role, we need to examine the contemporary imperialist system and its antagonisms.

The Imperialist World-System

There is a wealth of literature on the subject that explores the different motives and mechanisms behind modern imperialism, but the key aspect I would like to consider is underdevelopment.

There is a central imperative for capitalists to keep wages and resource prices low, in order for a continued increase of surplus value to accumulate. In the past, Western Europe depended on direct appropriation of resources and labour from the Global South through colonialism, which financed and industrialised both the home countries and the settler-colonial nations they founded. Modern imperialism does not depend on direct colonial control anymore; after the wave of political decolonisations in the 20th century and the rise in prices and commodities in the now-developed Global North, contemporary capitalism needed to keep cheap labour and resources flowing to the core without direct colonial control. Political independence was won in many struggles across the South, but economic independence was elusive; geopolitical, military and financial dominance allowed northern countries and corporations to artificially depress the prices of southern labour and resources, allowing them to buy products for cheap, and sell them back at a high-value to these poorer nations. These price differentials, fetishised by many as natural differences in market value, are in fact an intentional mechanism of obscuring the structural transfer of value from the South to the North; even as Northern countries reduced their manufacturing and focused on unproductive endeavours such as finance and consumption, they still reap the productive rewards due to imposed economic and political dependence on the South. There are a number of important scholars who have elucidated this system of economic extraction, the most prominent being Samir Amin, Aghiri Emmanuel, Charles Bettelheim, Walter Rodney, Immanuel Wallerstein and the recent studies by Jason Hickel; their work can be broadly defined as the theory of “unequal exchange”. Many factors contribute to the phenomenon: wage differentials, price differentials in products, Structural Adjustment Programs, international systems of tax evasion, wars at home and abroad…

I covered many of these (imperfectly) in my Masters dissertation Clandestine Capitalism, but I would recommend reading books and articles by any of these authors to gain a more thorough understanding.

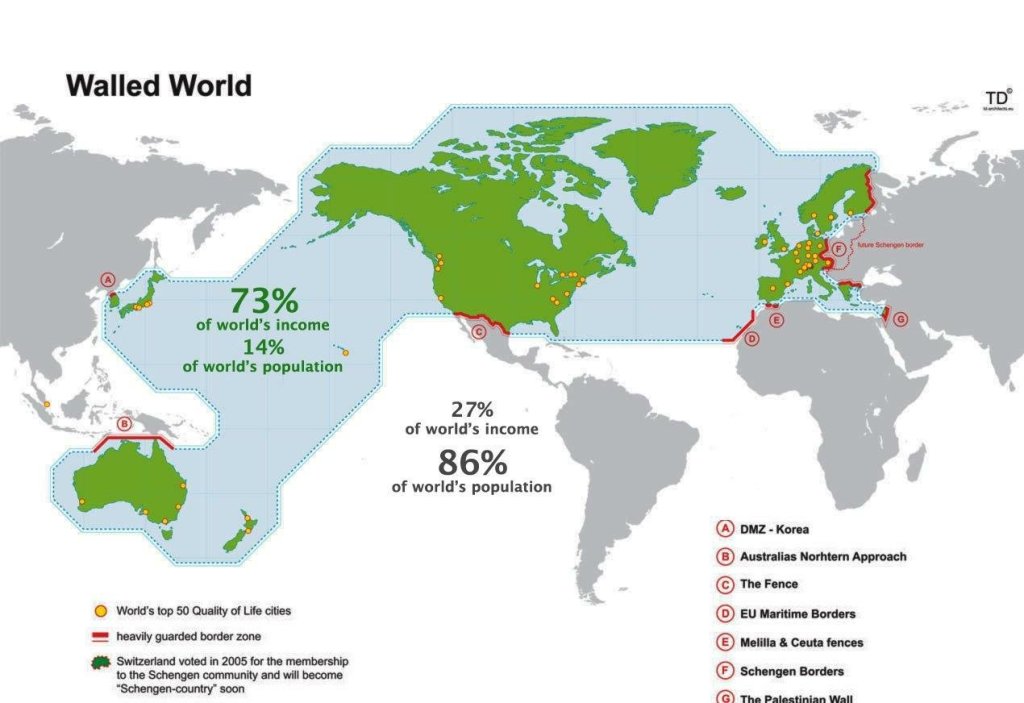

The neo-colonialist stratification of the world can be seen in the divide between the Global North and the Global South, which is not an accidental feature of geography, but rather an imposed legacy of imperialist conquest.

In the 1970s, the U.S dollar was established as the world’s reserve currency, which lent a major structural advantage:

World trade is now a game in which the US produces dollars and the rest of the world produces things that dollars can buy. The world’s interlinked economies no longer trade to capture a comparative advantage; they compete in exports to capture needed dollars to service dollar-denominated foreign debts and to accumulate dollar reserves to sustain the exchange-value of their domestic currencies.

To prevent speculative and manipulative attacks on their currencies, the world’s central banks must acquire and hold dollar reserves in corresponding amounts to their currencies in circulation. The higher the market pressure to devalue a particular currency, the more dollar reserves its central bank must hold. This creates a built-in support for a strong dollar that in turn forces the world’s central banks to acquire and hold more dollar reserves, making it stronger. This phenomenon is known as dollar hegemony, which is created by the geopolitically constructed peculiarity that critical commodities, most notably oil, are denominated in dollars. Everyone accepts dollars because dollars can buy oil. The recycling of petroleum-dollars is the price the US has extracted from oil-producing countries for US tolerance of the oil-exporting cartel since 1973 […]

The adverse effect of this type of globalization on the US economy is also becoming clear. In order to act as consumer of last resort for the whole world, the US economy has been pushed into a debt bubble that thrives on conspicuous consumption and fraudulent accounting.

– Henry C.K Liu, economist38

Dollar hegemony means that the U.S is able to borrow at lower interest rates, importing more than it earns from exports (by weathering deficits), and therefore, it is able to consume more products than its labour produces. These factors and others lent the economic strength and political hegemony to dictate international rules for their benefit, which forced the developing countries to open themselves up and sell their resources under “the free market”, which through mechanisms of privatisation, handed control over to the powerful forces of western capital and kept wages artificially low.

Wallerstein’s “world-systems theory” sees the global economy as being made up of core countries, peripheral countries and semi-peripheral countries; the core, the U.S and its Western proxies, possess the greatest economic resources and the most advanced technology, and use that advantage to extract cheap labour and raw materials from the periphery, which consists of the entire developing world.

The most crucial thing to understand is that the process of wealth accumulation depends on the systematic underdevelopment of poorer nations; the more that a country is sovereign, developed and producing for themselves, the more they consume their own resources. This raises the prices of resources and labour for the core, which constrains consumption and profits; this is why neoliberal globalisation imposed incessant debts through the IMF and World Bank onto underdeveloped countries to keep them economically stagnant, and why countries that refuse these deals have been subject to wars, coups and sanctions. The crucial difference between political independence and economic independence can be seen in the historical example of Haiti. After the slave revolt that gained them national sovereignty in 1804, the fledgling country was forced at gunboat to pay $20 billion in reparations to France, with the last payment being paid in 194739. Interventions, coups and occupations of Haiti have happened multiple times since the initial revolution, eliminating any possibilities for development; it was even exposed by Wikileaks that the U.S embassy and USAID prevented Haiti from raising its minimum wage from $3 to $5 a day40. For political revolution to be sustained, there has to be an economic revolution in the relation between those countries at the core of the world-system, and those in the periphery.

They are printing money. They are not manufacturing anything at all, it’s printing money. This has been one of their weapons globally – the monetary system… sanctions here, sanctions there… We need a new financial architecture globally.

– Isaias Afwerki, President of Eritrea41

This process of draining cheap labour from the Global South cannot continue forever. Contradictions inherent to the imperialist process mean that it is historically transient and destined to fall: now that the “rules-based international order” sold to these countries in the 1980s has shown itself to be a sham, the increasing viability and appeal of an alternative led by the periphery is becoming ever-more powerful. Whilst China and Russia serve as economic anchors for this “multipolar” order, many in the West condemn them as fellow imperialists, as replacing one hegemonic pole in the West with another in the East. This is understandable if the underlying systems and motivations of these countries are indistinguishable from the West, with their actions being an attempt at imperialism under different flags. I argue that by examining the historical evidence and their contemporary activities, another picture emerges.

The Peripheral Position of Russia and China

Some may balk at the idea of these two Eurasian giants being included in the periphery, but as Losurdo points out, the historical reality of both these countries shows that they are an “integral part of this greater third world”42; their current economic power leads many to forget the drastic changes that occurred in the last century.

In the time of classic imperialism, before the consolidation of the United States’ hegemony, the major threat to emerging imperialist blocs were other imperialist blocs that vied for control. This was the era of “inter-imperialist rivalry”, fights to determine where the basket holding the fruits of colonialism would lay.

WWI saw the UK, France and others being threatened by German expansion into Europe, with a similar dynamic causing WWII, a war conducted to prevent Nazi Germany from consolidating the continent’s wealth and turning Eastern Europe into a slave colony. These were not moral wars on the part of the West: Imperial Germany’s tools were derived from the United Kingdom’s colonial enterprise and the United States’ racist segregation and eugenics – the real problem was where these tools were being used. In reality, both of these struggles were to determine where the rest of the world (Africa, South America and Asia) would be governed from. The Germans hoped to rival the United States with a centralised Western Europe, a colonised East in Russia, and a subjugated Asian Pacific with the Imperial Japanese; in place of this vision, the United Kingdom and the United States wanted to ensure an Atlanticist control of the world sheltered from European competition. In light of this threat, it is easy to see why the United States was able to find common ground with the USSR, their communist enemy, in dismantling the German effort. As Truman said: “If we see that Germany is winning, we ought to help Russia. And if Russia is winning, we ought to help Germany and that way let them kill as many as possible.”43 Although this necessary alliance allowed the USSR to survive, despite the death of millions, it ensured American dominance and prosperity for the next stage in world history.

The question becomes, what made the USSR different than these imperial powers? Even though Russia was a minor imperial power before the Bolshevik revolution, this was a geopolitical position in constant threat of colonisation and balkanisation, with their continental size creating many enemies and their industrial development stunted by a decaying Tsarist regime. Russia was so backward at the start of the 20th century, that their subsequent worker-led modernisation and transformation into global superpower (without the aid of colonialism) would have come as a complete shock to those used to the status quo. Following the 1917 October Revolution, the Great Russian imperial system that subjugated the various ethnic regions surrounding the country was dismantled: the Bolsheviks that led it were explicitly anti-imperialist, both domestically and internationally, and the system was only overthrown with the support of oppressed peoples in Ukraine, the Baltics and Central Asia. The transformation of this minor power into a workers state in the wake of WWI, forced the European Allies to contribute troops and resources to the counter-revolutionary Whites, in an effort to crush the revolution in its crib. After the Civil War ended with the triumph of the Reds, and the subsequent Nazi effort to colonise the USSR was defeated in WWII, the pressure was on to contain this threat to the Western-led world-system. The USSR’s growing economic strength and material support for 20th century anti-colonial movements in the Global South fuelled the U.S’ aggressive opposition and encouragement of an expensive arms race that diverted funds away from national development. Skipping over a huge amount of history, in the end, these factors created the conditions for a stagnant economy and violent military coup in the USSR, bringing on the collapse in 1989. There was a real possibility after this event for an incorporation of the former Soviet Union into NATO and the Western system44, but this would have meant sharing the table with an economic rival in control of a huge amount of the Earth’s resources; better to keep the country isolated and weak than strengthen them as a junior member of the empire; this is also the underlying reason why countries in Africa, South America and Asia have been kept out of the core alliance. Shock therapy enforced by the IMF in the 1990s introduced a massive increase of poverty, a six-year drop in life expectancy and a new phenomenon of “homelessness” across the former Soviet Union, while 90% of industries were privatised and plundered.45 While the new Russian bourgeoisie made billions, the former state and military apparatus represented by Vladimir Putin organised with the national oligarchs to maintain Russian energy independence, when it was clear Western support was non-existent. Oil and gas production were renationalised, a federal Stabilisation Fund was established and Russia recovered to become a stable regional power run by a national bourgeoisie; economic and political sovereignty was settled, but their entanglement with the global capitalist system and their staunch opposition to Western interests led to the many contradictions we see today.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine cannot be separated from the violent 2014 Maidan Coup that implanted a pro-U.S regime in the previously neutral country, as well as NATO’s expansion towards the East, which in the 1990s was promised not to advance “one inch eastward”46. The morality of war cannot be defended, but we should try to understand the reasons behind conflicts rather than see them as inherently irrational or the machinations of a mad dictator. The reality is that the war was not initiated for short-term economic gain, as the fall in Russian billionaire’s wealth will attest; it was conducted for long-term defence against the potential of Russia’s balkanisation at the spear-tip of nuclear missiles: “they had gone to war not to gain more wealth, but to avoid losing what they had.”47 Military action, while terrible, does not categorise them as belonging to the modern phase of imperialism: as Jason Hickel shows in research quantifying unequal exchange, in 2018 “Russia was in fact among the most exploited countries, losing an amount of value through trade several times greater than India or Indonesia on an annual per capita basis.”48 With this in mind, we can see how the Cold War against the USSR, and the current proxy-war with Russia, cannot be classified as “inter-imperialist” due to Russia’s position in the world-system. In comparison to China, they have less ideological motivations and more political contradictions, but their material position is why Russia has continued to work with countries seeking sovereignty from U.S imperialism.

With regards to China, their history of being colonised by the British and Japanese in the “Century of Humilation” created mass poverty, addiction to British opium and repeated massacres by the Imperial Japanese, which resulted in a desperate fight for national liberation from nationalists and communists alike. This struggle against colonialism culminated in the Civil War and the ascension of the Communist Party, which sought to tackle chronic underdevelopment by directing production towards modernising the country. Leader of the political revolution, Mao Zedong, recognised that allowing the economy to stagnate would result in “only nominal and not actual independence and equality.”49 With this in mind, Deng Xiaoping’s attention turned towards equalising the global imbalance between the West and China, and preventing technological backwardness, through limited market reforms while retaining the commanding heights of the economy, such as banks and heavy industry, under socialist control. What lies beneath the Communist Party’s apparent capitalist reversal are the same factors that led Lenin to implement the NEP, which can be broadly summarised as the threat of underdevelopment. The decision to undertake limited market reforms was a necessary step to not fall behind the more advanced West; it is crucial to recognise that there was a crucial need for the development of the productive forces, incentives of employment for skilled technicians and import of key technologies that could only have occurred under the managed market economy.

The attraction of cheap labour in the 1980s meant that the U.S became dependent on China’s production capacity for cheap consumer goods, with the implementation of market reforms making imperial strategists optimistic for neoliberal takeover; their folly was ignoring the fact that the intransigence of the Communist Party gave China the option of refusing to stay in the periphery. Once it became clear that contemporary China had decided to raise the quality of their development, increase domestic wages and consumption, and pursue state-led suppression of Western capitalist interests, the U.S implemented a “pivot to China”50 under the Obama administration; their new fear became China shifting from the semi-periphery to the core, which would lead to an irreversible decline in American hegemony. Mystification of the PRC’s development path has led some on the left to see China’s market economy as synonymous with neoliberal capitalism, while those on the right denounce their state control over capitalists as “authoritarian communism.” The tactical decisions made by Deng Xiaoping and continued under Xi Jinping have resulted in unprecedented economic success and poverty reduction, and while it is understandable that the use of market mechanisms makes many uncomfortable, the evidence shows that the political power of the Communist Party reigns over the interests of capital oligarchy. While China does have billionaires, they do not have special privileges nor the ability to subvert the Party; many attempt shift the Party’s interests by joining and paying lip service, but none have been admitted to the Central Committee or inhibited state control of their assets.51 Billionaires are subject to anti-corruption campaigns that bring frequent arrests and sentencing, and those found guilty are imprisoned and their companies dismantled – cases that have never occurred in the capitalist West52. In reality, the financial system of the PRC is entirely state owned – China owns the four largest banks in the world (by asset value)53, as private banks only own 2% of China’s domestic banking assets; these are still highly regulated, with the 2023 Central Finance Commission being a new “super-regulator” that covers the entire sector.54 This means that no-one can move their money out of China to offshore trusts, an activity integral to wealth accumulation and the international bourgeoisie’s avoidance of tax. China’s land is 100% state owned and public, which means that land can be leased but not owned by private interests55; in conjunction with strong regulation of the real estate market, the Chinese home-ownership rate averages around a staggering 90%.56

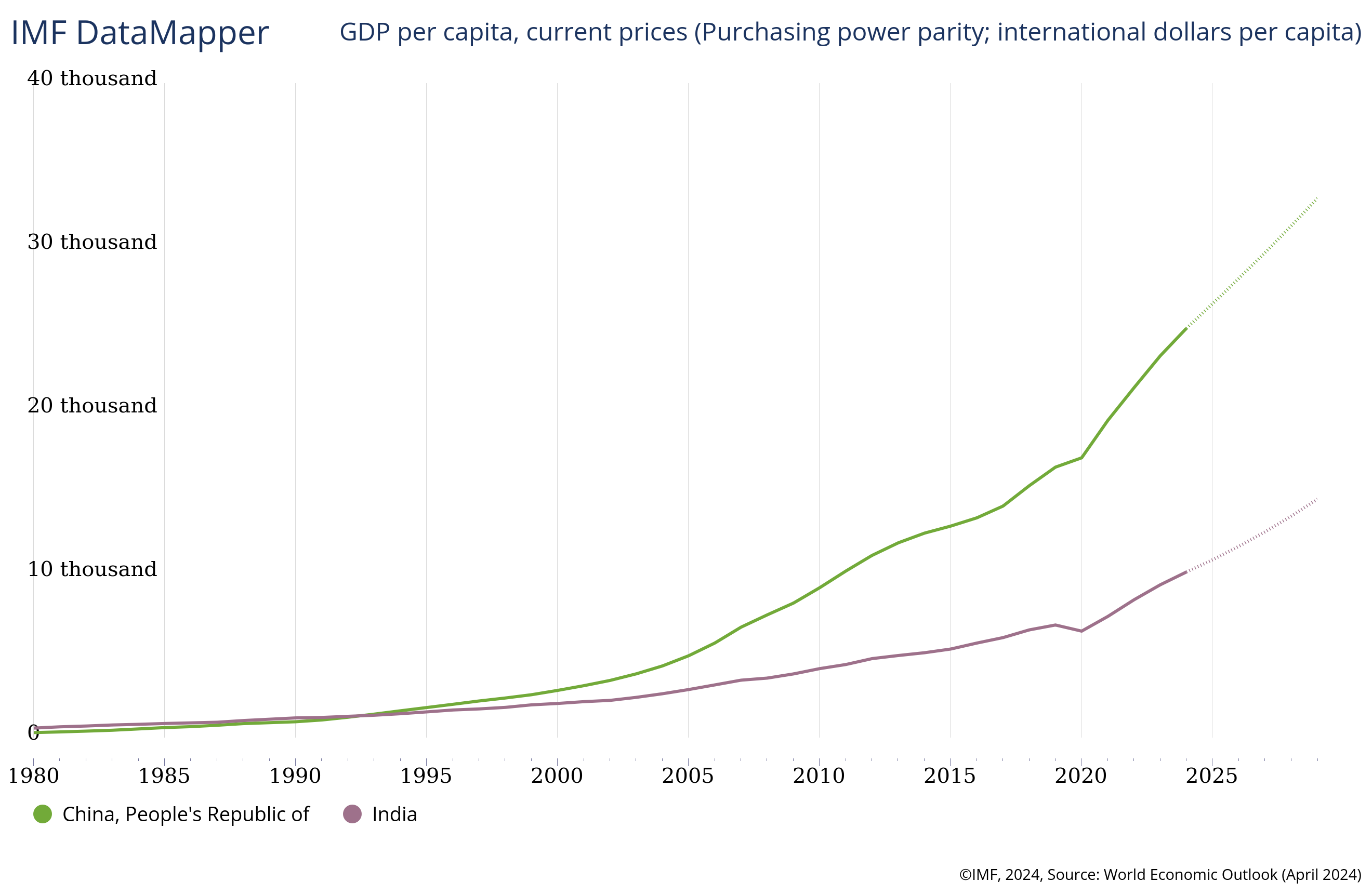

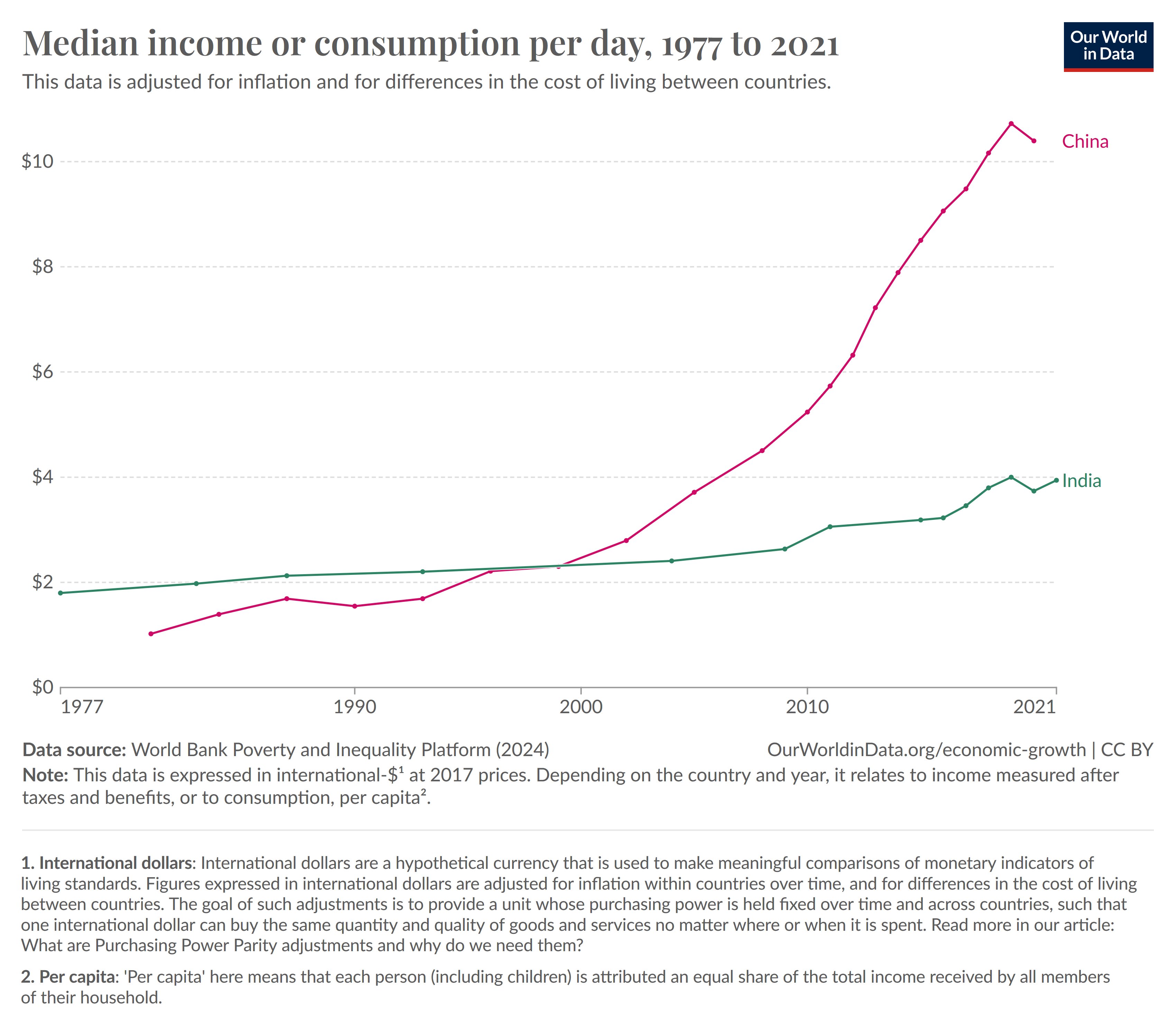

A stark difference lies between developing countries that have experienced a revolution, and those that still lie under the yoke of Western capital: as can be seen in comparisons between China and India.

In this data, we can see how stock market returns from India have sky-rocketed, whereas in China they have remained low and stable for thirty years. No-one would argue that India, a country still suffering from immense poverty and underdevelopment, is the stronger economy; yet from the point of view of Western investors looking to line their pockets, India is much more ripe for exploitation. A stark difference is also seen in the GDP per capita, median income and house ownership; these statistics exemplify the difference between an economy based on resource extraction and speculative finance, and a “real” economy, that maintains state control of corporations, raises productive powers and increases wages.

China’s domestic policy is a topic with immense depth, so for those who want more details, I will point readers to this selection of excellent books and articles.57

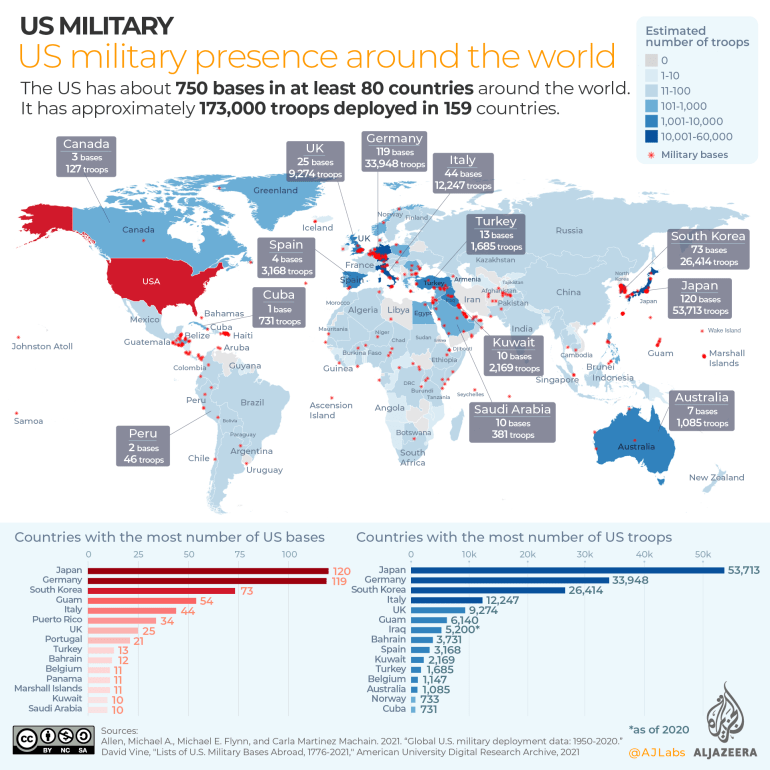

There is division in left-wing circles about whether this New Cold War between West and East is an inter-imperialist rivalry, but it is clear that economic sovereignty is what these countries are struggling for, not dominance of the Earth. It is difficult for Russia or China to be fellow imperialist powers, given the disparity of economic and military forces; U.S military spending is more than the next 10 countries combined, funding over 700 overseas bases – a simply incomparable number to the combined efforts of their enemies.58

In reality, this is a class struggle between neo-imperialism and the rest of the world, and the cause of the global turmoil we have seen this century. Israel’s brutal colonisation and Palestine’s countervailing armed resistance is a microcosm of this geopolitical landscape – there are structural reasons why the U.S and its allies are the only forces backing Israel’s warmongering in the Middle East, with the rest of the world on the side of Palestine. The U.S’ strategy of “divide and conquer” seeks to prevent de-dollarisation and economic development from occurring beyond their reach, whereas Russia and China’s efforts have been towards integrating the Middle East, Eurasia and the Global South as an economic bloc capable of resisting Atlanticist domination. This process is leading to the collapse of the “New American Century”, which is suffering both internal and external shocks.

Part 3: Hope Built on Certainty

The Imperialist Breakdown

One way that neo-imperialism is simultaneously imposed and undermined is the use of sanctions; the more that sanctions are imposed, the more that alternatives are being implemented – as many in the West are now panicking about.

Sanctions policy in Russia has been a complete and total failure. We thought that we would shrink the Russian economy by 10%, 20%, 30%, even 50%, yet weve shrunk the Russian economy by very little. And if you compare it to the performance of other regional economies, and let’s say in terms of the performance of its currency, it’s actually doing pretty well relative to other world currencies…

The foreign policy establishment claimed that one of the strongest sanctions measures was the disconnection of Russian banks from SWIFT. Scholars claimed that this would kneecap the Russian economy. But while the Washington foreign policy establishment was preoccupied with crafting a sanctions regime, they failed to consider that Russia had been developing their own alternative to SWIFT, which is of course the SPFS…

My concern is that our Ukraine policy has had this massive, unintended consequence. And if we had gone into this 18 months ago knowing that we would be pushing Russia and India closer to the Chinese – were encouraging the creation of an entirely alternative financial system – it’s really important that our law enforcement has access to some of these financial transactions. It’s one of the ways we catch international crime. It’s one of the ways that we prevent international terrorism. If the consequence of our Ukraine policy is weakening that financial system and strengthening an alternative financial system, I think it’s one of the many consequences for our country that our policymakers haven’t fully incorporated.

– J.D Vance, U.S Senator & Donald Trump’s VP in 202459

Alarm about sanctions’ rise has reached the highest levels of the U.S. government: Some senior administration officials have told President Biden directly that overuse of sanctions risks making the tool less valuable. And yet, despite recognition that the volume of sanctions may be excessive, U.S. officials tend to see each individual action as justified, making it hard to stop the trend. The United States is imposing sanctions at a record-setting pace again this year, with more than 60 percent of all low-income countries now under some form of financial penalty, according to a Washington Post analysis.

– Jeff Stein, Federicca Coco, via Washington Post (emphasis mine)60

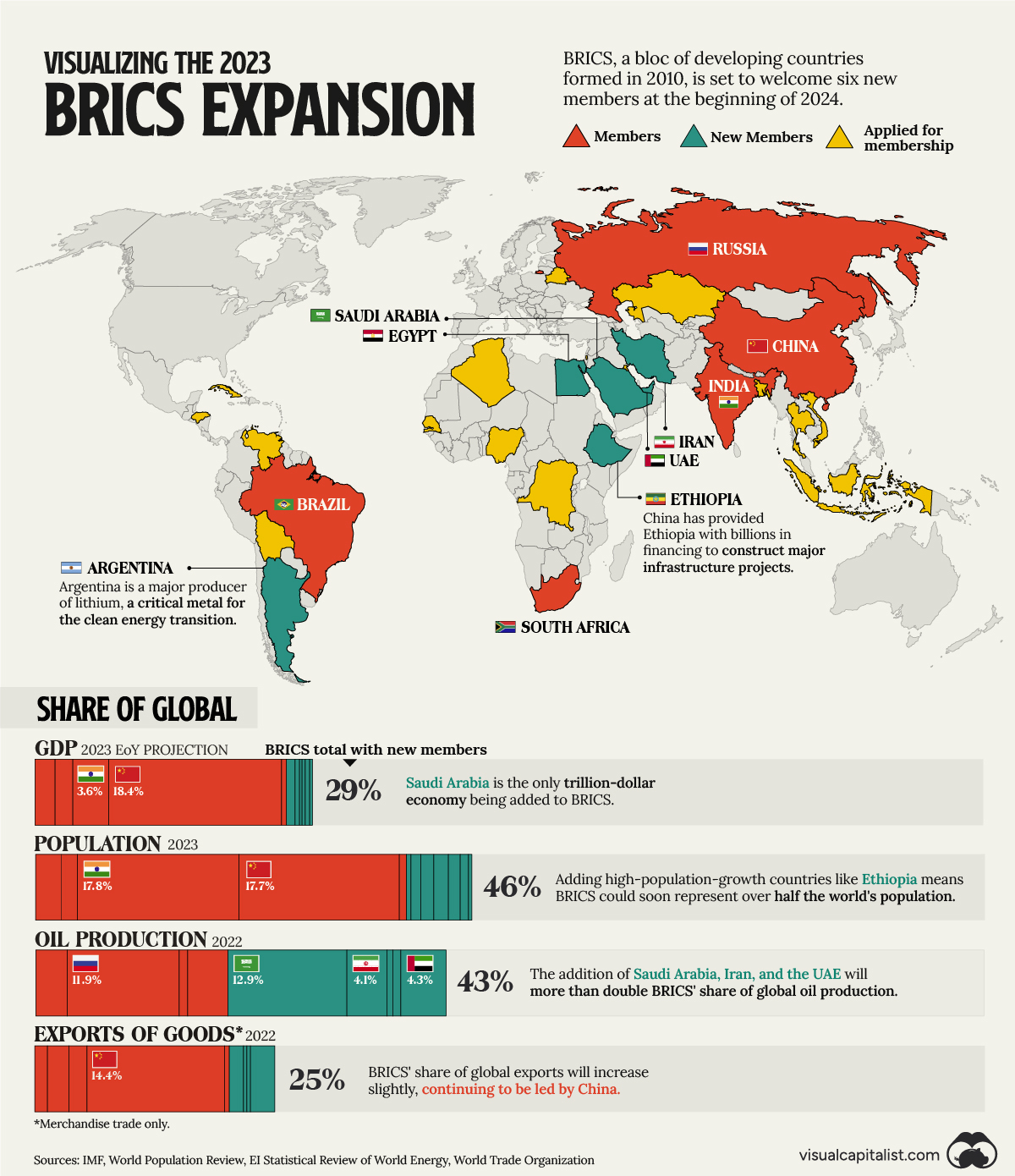

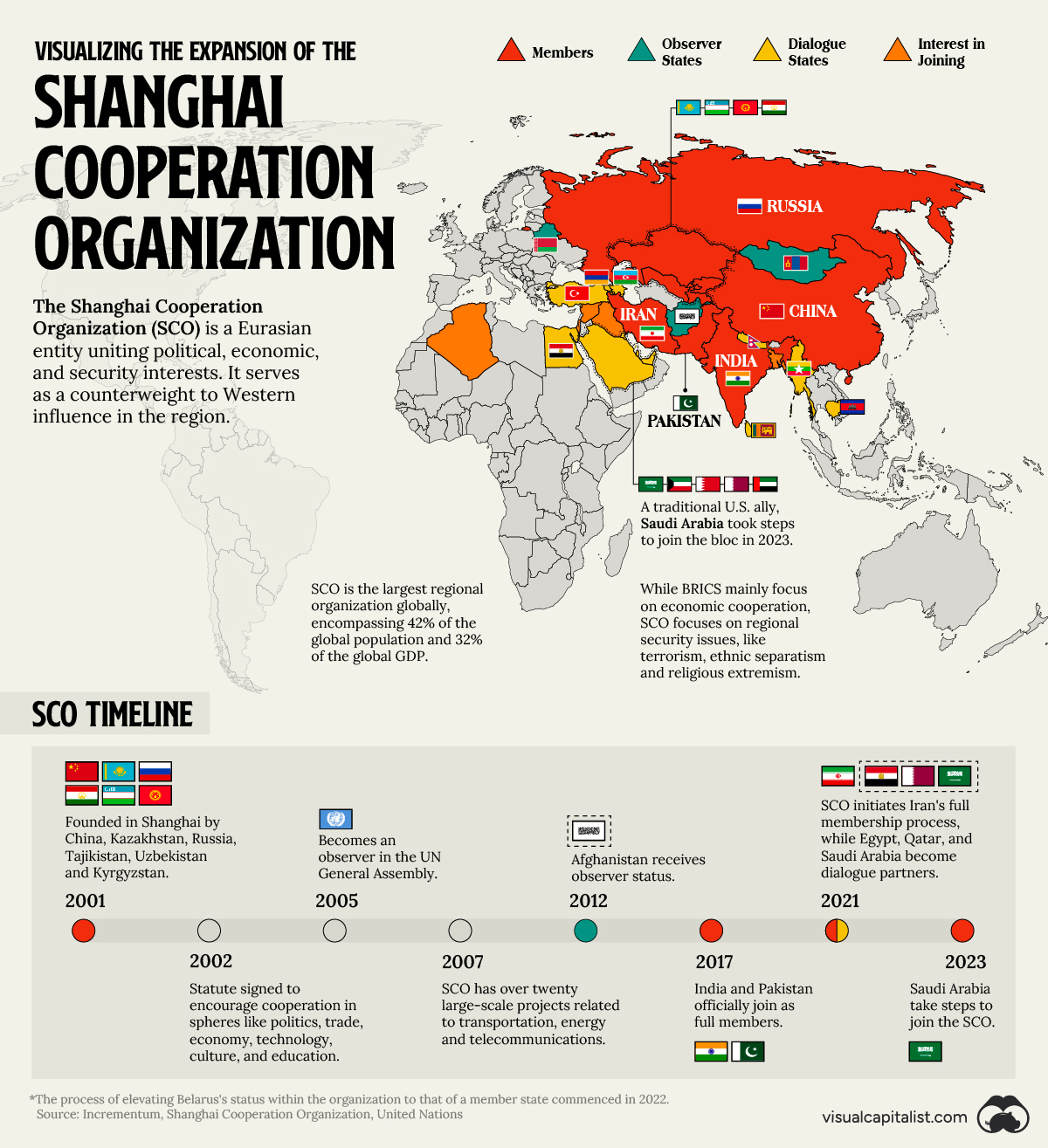

Now that the majority of countries in the world are feeling the pressure, alternative arrangements such as the development of a new payments system, as well as bilateral trade agreements with Russia and China, are becoming a concrete reality. The coalition BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, as well as others), a bloc explicitly aimed at bringing together developing countries, is offering a viable path towards economic sovereignty. While it is not as strong of a coalition as the NATO countries, it is an embryonic institution that allows these oppressed nations to solidify their relations with each other, work out the antagonisms between them, and further the emergence of the new world order. Nations such as Saudi Arabia and Iran, enemies in recent memory, are now conducting joint military exercises; this marks a large shift in international relations, with BRICS acting as a crucible.61 While BRICS mainly focuses on economic cooperation, another alternative structure being built is the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, which focuses on security issues such as terrorism, ethnic separatism and religious extremism. This serves as a counterweight to Western influence in Eurasia, with Russia, China, Iran, India, Belarus and others joining the organisation.

Another positive process now occurring is that oppressed countries have been encouraged to develop domestic production, under the pressure of the very sanctions meant to inhibit them:

- After 14 consecutive quarters of agricultural growth, 97% of Venezuelan food is now being produced domestically, despite continued U.S pressure.62

- The small island nation of Cuba has implemented one of the world’s best healthcare systems, under one of the most stringent sanction schemes ever imposed.

Cuba’s model demonstrates that with political commitment to health equity and strategic investments in public systems, remarkable improvements are feasible even with constrained resources. Components like equitable access, robust primary care, localized innovation, and social medicine principles remain relevant for developing countries seeking pro-poor reforms.

– Aly Dramé, Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology 63

- Sanctions on Russia have inadvertently strengthened their economy in the long-term, even being described as “a gift to the Russian economy.” As U.S economist James K. Galbraith argues, the massive withdrawal of Western companies from the Russian market forced them to sell assets back to Russian companies, who bought these with Russian loans for “very favourable prices”; this transfer of Western capital wealth to Russian domestic ownership is bolstered by the country’s low resource costs, leading to more economic growth.64

Kazankov […] is a great supporter of Western sanctions: “They’re an incredible developmental tool for Russia,” he told me. “The West should have imposed them back in the Nineties. We’d be the engine of the world by now. Too bad.

– Russian farmer, quoted by Marzio G. Mian65

- China has beaten the U.S trade war to produce domestic high quality semiconductor chips, one of the largest obstacles to rising up the value-chain. One of the most coveted prizes in manufacturing, the most advanced chips are being produced in secret locations in the Netherlands and Taiwan; it is now clear sanctions aimed at maintaining this superiority have failed, with domestic Chinese chips already powering entirely homegrown smartphones and computers.66 Many other success stories in science, technology and production abound despite U.S pressure – China’s predominance in electric vehicles67, renewable energy (twice as much as the rest of the world combined, with more than 80% of the world’s solar manufacturing capacity)68 and scientific innovations69 have become undeniable.

Further cascading failures include the U.S’ inability to project military power across the world. The return of the Taliban in Afghanistan, the lack of regime changes in Syria, the DPRK, Venezuela and Iran, as well as the on-going success of Yemen’s blockade against Israeli ships in the Red Sea, is a testament to the real deterioration of imperial power.

The result of this can now be witnessed in the Red Sea. If the US Navy cannot even lift a blockade by Yemen, one of the poorest countries in the world, the idea of lifting a blockade around Taiwan is a complete fantasy. If the US cannot compete with the arms production of Iran, then the notion of somehow out-competing China should be put to bed immediately.

[…]

But this is also why the Red Sea defeat will be met with silence.

More than any other conflict raging today, it highlights the crisis within the West’s military organisation, as well as the fact that there is no real way to fix it. To admit our powerlessness is to admit that the era of Western hegemony is already over. Faced with little alternative, we will continue to let the Houthis blow up our ships – and then pretend that none of it really matters.70

There is even increasing discontent from the U.S’ allies over their political desire for hegemonic control, which often come into conflict with the economic desires of Western corporations. Europe is in an uncertain place, as their political alliance with the U.S conflicts with the economic benefits that come from integration with the larger Eurasian bloc; the U.S sells natural gas at a far higher price than the Russians71, and with the possibility of increased tariffs on Chinese products, companies such as Mercedes and Volkswagen have been lobbying to block them from occurring due to their large production dependencies and market access to the country.72 Thousands of U.S companies have built their supply chains and factories inside China, with the country being “the main supplier of imported goods [to the U.S] and second-largest foreign holder of its public debt”, so the recent push for a complete “de-coupling” is an unlikely fantasy.73 Another strain within the Atlanticist bloc is discontent from core allies such as Japan and South Korea, that do not get equal economic privileges from the U.S, despite promises of a free market; the buyout of the failing U.S Steel by Nippon Steel has been blocked by U.S legislators, raising concerns of preferential treatment and managed competition.74 In an ironic twist, the Communist Party’s control of China’s economy means that companies are allowed to go bankrupt and be bought out by the state, which allows their assets to be distributed to other companies and projects; this process is a more dynamic and competitive market than in the country where private interests reign supreme, who cannot help but bail out failing banks and companies at the tax-payers expense, creating recurrent failures and incentive for private monopolisation. Analogised to sports, it is like having a fair referee overseeing the game and ensuring healthy competition, rather than a corrupt arbitrator bending the rules towards one team.

As we can see, there are clear signs of the proclaimed “New American Century” evaporating in favour of a resurgent Eurasian and Global South bloc, led by the countries making up the BRICS coalition. Regardless of personal opinions towards these nations, it is obvious that the U.S is trying everything it can to prevent the rise of this new balance of power, with the next ten years being a “decisive decade”.75 For the new order to not wither away, the system of extraction and suppression that has led U.S dominance has to be eroded; this can only occur by allowing underdeveloped countries in the Global South (predominantly in Africa and South America) to develop in a sovereign manner. Are any countries able to facilitate this, and what is their motive for doing so, if not driven by hegemonic ambitions?

China’s Efforts to Combat Underdevelopment

Let me summarise it and take up a little more of your time; it is not predestined that a powerful nation will inevitably become a hegemonic; rather, it is a law of history that hegemonic nations will inevitably decline. If a major and powerful country insists on pursuing hegemony and bullying the weak, it is bound to fall sooner or later. So for the countries in our Asia-Pacific region, ignoring the broader trends and engaging in fraternal disputes will only make the path narrower and more difficult. Only by going with the tide and working together can we open up a broad and promising road ahead. What I want to say is that culture is not just Coca-Cola, and it’s not as if one country’s formula must decide the flavour of the entire world. In this regard, if we view things from a zero-sum perspective, then everything everywhere becomes a competition or a game of winners and losers. But if we look at it from the perspective of a shared future, then opportunities for cooperation are present everywhere, all the time. Thank you.

– Chinese Major General Wang Xin

11th Beijing Xiangshan Forum, September 13, 202476

China is not just trying to create an alternative world order.

It is succeeding.

Many in the West cannot gauge the success China is having in the rest of the world.

– Asset Management analyst in the Financial Times77

What we get from China is an airport.

What we get from the United States is a lecture.

– Former U.S Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, quoting an anonymous person from a developing country78

The history of the United States as a settler-colonial state is intertwined with their contemporary drive for imperialist domination, but this is often obscured; many academics project chauvinistic motives onto any nation of a given size, fetishising self-interest and greed as a fundamental and unavoidable aspect of international relations. It should be obvious that countries with a history of colonisation are less susceptible to these impulses, especially ones governed by parties with an explicitly anti-imperialist bent. Fears of Chinese imperialism take for granted that all nations have similar worldviews to those of Western colonialists, or that they have an inherent self-destructive tendency towards war. Though this could conceivably change in the future, we should keep in mind that China has not gone to war with a foreign nation for over 40 years; the only wars conducted since the Communist Party came to power have been in Korea and in Vietnam, both anti-imperialist struggles and examples of U.S defeat.

One prominent scholar of International Relations, Professor John Mearsheimer, holds a pessimistic view of great-power relations and is sceptical that China is going to be able to have a peaceful rise in face of US aggression – in 2005, Mearsheimer stated what he sees as axiomatic to world powers:

The best way to survive in such a system is to be as powerful as possible, relative to potential rivals. The mightier a state is, the less likely it is that another state will attack it. The great powers do not merely strive to be the strongest great power, although that is a welcome outcome. Their ultimate aim is to be the hegemon, the only great power in the system.79

This zero-sum view, a perspective incompatible with peaceful development, is inherited from a European history of countries constantly at each others’ throats; the American view of world relations has no room for compromise or peaceful co-existence, with U.S Secretary of State Anthony Blinken stating: “If you’re not at the table in the international system, you’re going to be on the menu.”80 This is in sharp contrast with the thought of Dr Zhang Yunling, a Chinese scholar of International Relations, who emphasises that “there is no existential threat to China” and that “as scholars, what we need to do is restrain China’s egocentrism. After World War II, the US established its absolute dominance. By contrast, China’s rise is occurring in a new environment – one that places certain constraints on it.” These limits mean that hegemony is no longer possible nor desirable: “China does not seek to replace or defeat the United States, but the US worries that it will be replaced. China hopes to change the world, while the US is concerned about the direction of this change.”81 Wang Yi, Chinese Foreign Minister, echoed these thoughts: “Those with the bigger fist should not have the final say. And it is definitely unacceptable that certain countries must be at the table while some others can only be on the menu.”82

If China has different foreign relations than the U.S, this mindset should be evident in their actions; one area in which we can demonstrate this is in the role of China in combatting underdevelopment.

An invaluable resource for understanding China’s foreign activities is Kyle Ferrana’s Why the World Needs China: Development, Environmentalism, Conflict Resolution & Common Prosperity, with Chapter Six, China and the World, being an incredible piece of work that I cannot hope to condense in this short section. Due to this being an essay on my website, with no obligations to anyone, I will recommend something unorthodox. I would recommend that the reader buy his book, read that chapter, and then come back to read the rest of this essay. I will summarise the broad thesis, but for a proper analysis, I implore the reader to consult Ferrana’s book, which is one of the most clarifying I have read and not a propaganda piece; an honest analysis will recognise the contradictions that always exist in a given situation, and so Ferrana does not shy away from the fact that historically “the PRC’s relations with African countries are not above reproach”83, as they have used the same structures of international trade to utilise cheap resources and labour. However, despite this initial bitter taste, Ferrana makes clear that China’s relation with Africa is vastly different to the imperial core:

Given its complicity in the most significant mechanism of exploitation, it must therefore be asked if the PRC has become a partner of the super-empire, seizing for itself its own neocolonies?

[…]

The answer [is] negative.

[…]

An updated calculation for the year 2016, using both Köhler’s formula and his sources, yields an increase in unequal transfer value from the same group of African countries to China, yet the total was just 0.76% of their GDP. Today, as mentioned above, with only a few exceptions, the PRC is the largest trading partner of every African country, yet overall, the terms of this trade are likely thus far only very slightly in favor of China.

[…]

The PRC’s principal sin, therefore, is that its industry has taken a step up in the economic value chain. It buys raw materials at the same grossly undervalued prices (i.e., extracted in African mines with vastly under-compensated labor) that the West does, yet the super-profits of this exchange still flow almost exclusively to the West, as Chinese manufacturing transforms those materials into commodities and sells them also at grossly undervalued prices. Indeed, the PRC cannot acquire these materials much more dearly, for its market dominance in commodity manufacturing has only been possible by underselling Western manufacturing. The price gap between cheap Chinese goods and expensive Western goods can only be derived from an equivalent gap in the price of labor power, meaning that China’s newfound wealth has come from the labor of Chinese workers, and not at the expense of African workers – whose exploitation is severe but unchanged – but at the expense of Western domestic industry. Thus, through this cycle of relationships Africa has remained poor, China has grown gradually richer, and the Western financial oligarchy have seen no reduction in their obscene super-profits.84

This demonstrates how China is the country at the semi-periphery of the world-system; flows of wealth from Africa go overwhelmingly to the Western financial oligarchy rather than to the PRC, but enough is gained in the process to reinvest in state-led production; this allows for economic mobility and intelligent competition with the imperial core. What should be emphasised is that this reinvestment is not merely domestic – China are not just improving themselves through this dynamic, they are actively raising the periphery to their level of development.

[…] the PRC’s net investment income from abroad is negative; in fact, according to World Bank statistics, with the relatively modest (around $13 billion) exception of 2014, the PRC has not had a positive net primary income from abroad (that is, all income from the PRC’s investments in other countries minus payments on foreign investments in China) in any year since it first became a major capital exporter in 2008, and had an overall loss of more than $700 billion over the entire period recorded by the World Bank. In 2018, a typical year for the decade, the PRC’s net primary income stood at negative $61 billion; in contrast, in the same year France had almost $65 billion in positive primary income, and the United States—which has never had a negative net primary income from abroad in any year recorded by the World Bank—had nearly $300 billion. China, it seems, is home to some of the richest finance capitalists the world has ever seen—but also either the most patient or the most blundering. They have made enormous and increasing investments in the rest of the world, but so far turn only an abysmally low profit from their objectives, it is clear Chinese investments qualitatively differ from those of other major capital exporters.85

These indications of a different economic strategy are reflected in the physical achievements that have occurred. The most obvious example is the Belt and Road Initiative: launched under Xi Jinping in 2013, the BRI has invested more than $1 trillion into the Global South, “sign[ing] over 200 cooperation agreements with over 150 countries and 30-plus international organisations across five continents”. As writer Richard Brek describes:

Some of the fruits of this investment include: a $6 billion railway connecting Laos and China; the El Hamdania Central Port, Algeria’s first deep-water port; a railway and water pipeline connecting Ethiopia and Djibouti; a Chinese industrial zone in the Gulf of Suez; a manufacturing hub near Addis Ababa; the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya; the provision of satellite television to villages in Nigeria; the establishment of freight rail services connecting China to forty-two European terminals; a significant expansion of Azerbaijan’s Port of Baku; infrastructure development across Central Asia; Indonesia’s first high-speed rail line; an airport and bridge in the Maldives; and a shuttle train to transport pilgrims during the Hajj in Saudi Arabia. That list doesn’t even touch on the Americas, where BRI has also had a substantial impact.86