DISCLAIMER:

This is an essay I wrote for my Masters degree in 2023, part of a series I will be putting on this site to get me started. While I have changed some of my views and found new lines of inquiry since I wrote this, I feel there is value in it and after reading through it, I am still happy with its quality and its accessibility for new readers. It is heavily indebted to Ian Wright’s work on undecidability (of the blog Dark Marxism, not the footballer), with some of the similarities being far too close for my current standards, so I will link to the talk that inspired this in the bibliography as a small penance. Many thanks to him for corresponding with me and offering feedback; I’ll just say that I now have far less restrictions on my time and mental capacity than I had in university – I have changed my habits accordingly. Despite this, I hope that this “legacy essay” condenses and clarifies some of his points, as well as taking inspiration from elsewhere, such as Douglas Hofstadter’s work. There are tangents to follow and additional information I could add to the arguments, so I might revisit it in future and create a REDUX edition after I finish new material I am working on. In the meantime, I hope you enjoy the essay in its current state.

Thinking about Thought:

Self-reference in Computing and the Identity of Thought and Being

The aim of this essay is to analyse the question of the identity of Thought and Being; many philosophers have questioned whether the structure of thought offers insights into the structure of existence, and if they are intrinsically related. I show our attempts to simplify thought to its barest essentials have the tendency to collide with our attempts to simplify base reality to its barest essentials. This is a perennial problem in philosophy, and arguably the principal question in thinking about the relation between epistemology (What can we know? How do we know?) and metaphysics (What is the fundamental nature of reality?).

Thinking about thought drives at the essence of ourselves, so it is natural that it leads to questions about our fundamental existence. I examine two examples that show how this self-reflexivity can produce these results: Hegel’s The Science of Logic, and the “computability thesis”.

An important clarification to make, is that in this essay I will not be discussing problems of consciousness, but instead problems of the structure of thought. This means this is not an essay concerned with concepts in Philosophy of Mind such as qualia; rather, I will be examining how these philosophical theories of the basic logic of our thinking, create interesting ontological questions. Thus, the question of how or why thought is conscious, is not the immediate problem.

In The Science of Logic, Hegel sought to discover the fundamental categories of thought that structures our reality, and in doing so, he claims to capture the structure of everything; all from the pure reflection of thought. Hegel attempts to derive this structure from logical necessity, a method based on his critique of Kant, who lacked a clear derivation of his categories of thought. Hegel’s identity of thought and being asserts the distinction collapses between the most basic element of thought (“pure knowing”) and the most basic element of existence (“pure being”), after both are reduced to their minimum intelligibility. For materialists and empiricists, this seems like a fool’s errand; surely our thought merely attempts to apprehend the complex outside world, rather than being intimately linked with it? However, materialism does claim that our brains are embedded in the same material substrate as the rest of the universe. Substance monism is generally assumed in science, rather than the problems of Cartesian substance duality or inaccessible Kantian noumena. Therefore, it is valuable to think through the possibility that our cognition must share at least some fundamental properties in common with everything else. For this reason, I examine Hegel’s method and the resulting logic that arises. Primary sources will be the George di Giovanni translation of The Science of Logic, (2010) and Stephen Houlgate’s The Opening of Hegel’s Logic: From Being to Infinity (2006), which references the Miller translation.

I will then explore a different example of how “thinking about thought” leads to questions about Being, through how a form of human cognition (“human computing”) has been abstracted into a seemingly universal mechanism – the computable algorithm, later defined formally in the Church-Turing thesis. I will show how questions like: “what can computers compute?” and “what can computers not compute?” led to questions about whether what humans can compute is identical to computers. This will lead to the “physical Church-Turing thesis”, also termed the “computability thesis”: the idea that there is a deep relation between physical reality and computability.

This will involve discussion about the notion of “undecidability” and whether we can prove an identity of computational thought and computational being. I show throughout that because of modern attempts to find the minimum intelligibility for logical reasoning, just as Hegel did, we have returned to the philosophical problem of the identity of thought and being. The primary source will be Borut Robič’s The Foundations of Computability Theory (2020).

In the final part of the essay, I will draw links between the two examples, with reference to Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach. This book is infamously fascinated with computing and thought, with Hofstadter claiming that complex tangled hierarchies of rigid logic “bootstrap” the mind, due to systems becoming self-referential. I will demonstrate how Hegel’s similar fascination with the logic of self-reflexive thought and contradictions becoming “sublated”, shows a clear correlation with the insights of computability theory.

What was The Science of Logic trying to achieve?

Hegel’s aim with The Science of Logic was to continue of the project of German Idealism, where figures like Kant, Schelling and Fichte were attempting to derive the basic categories of thought. They sought to figure out the basic structures of thought that create our consciousness and language, formalising our flows of experiences into intelligible abstract categories that have causal relations between each other. Rather than basing this on sensations themselves, this school of philosophers wanted to pin down the nebulous forms of thought into defined concepts like “reality”, “cause”, “form” and “existence”. Their claim was that for the mind, without these unconscious concepts, we would be incapable of understanding or comprehending what we perceive. As Hegel said:

“the activity of thought which is at work in all our ideas, purposes, interests and actions is… unconsciously busy”

(Houlgate, p.10, quoting Miller translation 36/1: 26).

Kant was the first to try to obtain the basic units of thought that create our experience, and he saw thinking as fundamentally discursive, based in language. Thoughts and apprehension of objects never arise by means of pure intellectual intuition; they are given to us in logical structures. The method as to how he derived his twelve categories of thought was from “judgement”, which is the minimum unit of intelligibility for Kant. Judgements are the various ways we connect subject and predicate, e.g X is Y. Thinking is usually more complex than this, but Kant claimed that thinking cannot be less than this. For example, the hypothetical judgement “If X, then Y”; to think of an object in this logical form is to think of an object as an “if”, rather than a “then”, a “ground” rather than a “consequent”. A ground can also be termed a cause: therefore, the category of “cause” is simply the thought of an object determined in respect to the hypothetical form of judgement. This is not how Kant derived all his categories, but you can see the form of the method he used. Kant did not seek to find all the possible categories, because his aim in the First Critique was to investigate the role the categories play in providing the conditions of experience, rather than the specific method of how to derive them. This is where Hegel’s critique points to: Kant got ahead of himself, and did not derive the twelve categories from the very nature of thought itself. In essence, Kant was too arbitrary in his methodology to get there rather than committing to logical necessity. Hegel wanted to follow the logical structure of thought to reveal the categories organically, whereas Kant found them empirically and gave no reason as to why some categories were necessary and some were not. He saw Kant as both taking for granted that “concepts are always predicates of possible judgements”, and that they would be found in formal logic. Kant saw philosophy as the articulation of rules governing the thinking of objects, before the thinking of objects themselves; Hegel saw it as the opposite, with philosophy discovering the categories before articulation, with no presupposed method.

“Logic, therefore, cannot say what it is in advance, rather does this knowledge of itself only emerge as the final result and completion of its whole treatment. Likewise its subject matter, thinking or more specifically conceptual thinking, is essentially elaborated within it; its concept is generated in the course of this elaboration and cannot therefore be given in advance.”

(Giovanni, p.23, emphasis mine)

Thus, Hegel wanted to dig deeper, to figure out how categories arise out of the most basic undetermined unit of thought. Hegel’s era was one of radical scepticism, a scepticism towards traditional religion, ideology and authority; he saw the solidification of the Reformation, the radical novelty of the French revolution and the industrial fruits of the Enlightenment all within his lifetime. This is why Hegel wanted the categories to be derived and revealed by logic naturally, but at the same time, they needed to be derived by dropping all prior assumptions about logic. Arbitrary assumptions about thought, any at all, thus needed to be completely excised. This meant that for Hegel, even Descartes’ supposedly basic starting point “I think, therefore, I am” makes too many wild assumptions: it assumes the “I” exists. The project of the Logic is to derive the basic categories of thought, supposing nothing about thought, except that it is “sheer indeterminate being”. For Hegel therefore, the formula goes:

“Thinking, therefore, Being”.

Hegel’s starting point is this unity of thinking and being, that arises from dropping not just all extraneous assumptions, but all assumptions. Thinking at this most basic point, is just Being, and at this point Being is “without any further determination”. Hegel’s identity of thought and being asserts a coincidence between the most basic element of thought (“pure knowing”) and the most basic element of existence (“pure being”), after both are reduced to their minimum intelligibility. This reduction means that they collapse into one another; thus, this duality between thought and being is more accurately described as non-duality, known as “pure being”.

“In its indeterminate immediacy, its equal only to itself; it is also not unequal relatively to another. It has no diversity within itself nor any with a reference outward.”

(Houlgate, p.79, quoting Miller translation p.193)

It is so indeterminate that you cannot call it the being of thinking, because it is so indeterminate and empty: it is a pure lack. The determination of “no diversity” is not a determination: Being is not defined as that which lacks diversity, or as contrasting with diversity, but rather Being as completely absent. Later in the Logic, Hegel has categories which include within themselves, that which they exclude, for instance, identity as the pure excluding of difference. However, for “pure being” this is not even the case. For instance, Parmenides attempted to stabilise his theory of “Being” by defining it as that which can be thought, juxtaposed against “Nothing”, which cannot be thought. For Hegel, it is not that “Being” cannot be thought (it is thought), or that it is “not nothing” (as we will see, it is also nothing): it is so indeterminate that it cannot be determined as indeterminacy. It could be called pure “isness” as Hofstadter does, or Zen, but any term is already too determinate:

Being, is Being, is Being…

This search for systematic rigour is what leads Hegel to “Being” as his starting point; however, you cannot even call this a starting point, because a “beginning” presupposes a continuation. In a paradoxical twist, it is the direct opposite of a beginning, which is where Hegel’s system starts. Hegel recognised that philosophers in the past often chose a determining principle to begin their whole philosophical system. For the Pre-Socratics, there were concepts such as “water”, or “the One”, or “the Good” that they assumed were necessary for philosophy. This assumption obscured “the need to ask with what a beginning should be made, [as this was of] no importance in face of the need for the principle in which alone the interest of the fact seems to lie, the interest as to what is the truth, the absolute ground of everything”. (Giovanni, p.45) Instead of assuming a beginning, Hegel attempted to problematise its very concept to drive at a deeper dynamic.

Now before we explore how Hegel managed to use “true being” to (not?) begin, one may ask, how is his formula of “thought is being” without assumptions? If Hegel is attempting to have a presuppositionless starting point, then:

1. Is Hegel not presuming the existence of thought and being?

2. Is it even possible to have no presuppositions?

The next section will briefly cover why in his attempt to convey Being as this indeterminate indeterminacy, Hegel must rely on some basic assumptions to express his thought in a coherent manner.

Hegel’s Presuppositions

For Hegel, it is self-evident that to articulate the development of a thought, it needs to be in language. Whether this is natural language or mathematical language, he agrees with Kant that language is how thought is developed and expressed. But in the case of thinking about thinking itself without mediation, how do you write this in a mediated way to explain its emergent properties? A tool that Hegel employs to reach this elusive goal is the “speculative sentence”, which uses a chain of sentences where the nature of the subject being discussed emerges from the series of thoughts. Unlike Kant’s judgements, which have a fixed subject and predicate, Hegel’s articulation allows the predicate to clarify the subject organically; rather than saying “there is a book; the book is green”, Hegel uses very complex and long trains of thought that, while exposing language’s insufficiency, allow him to direct one’s thinking in a certain way. To think “pure being” in the way Hegel desires, one needs two faculties: on one hand, you need to understand language and its complexities in order to follow his logic; and on the other, you need the ability to hold all language at bay. All the implications of thought need to be set aside at times, whereas at other times you need to keep track of a specific train of thought. Hegel’s Logic means that you cannot assume any laws, because the point of Hegel’s Logic is the presuppositionless starting point; yes, dynamics and laws emerge as we will discover, but they will change as the train of thought moves. Hegel uses a term in German, translated as “letting-hold-sway”, that helps define his philosophy as one of passivity, letting the matter at hand express itself without interference. Paradoxically, this passivity is an action itself, and requires effort. For the Logic, he borrows Fichte’s idea of “thoughts emerging before your very eyes”, which is approximate to the way science develops. There is often an exclamation of “eureka!” or “Oh! That’s what this means!” in discovery; Hegel wants the same for philosophy, for his concepts to emerge as an imminent development. Instead of philosophy being defined as “thinking about Being”, which science has already staked a claim in, Hegel argues that the philosophical subject’s true innovation is how we can “think about thinking about Being.” This recursive step is crucial in both Hegel’s philosophy, and as I will discuss, in computational theory. Thus for Hegel, language is ultimately necessary to record his thoughts, despite it being an obstacle to his reasoning.

As for the possible presupposition that “thinking is being” represents, of the relation between the two terms, Hegel believed that the state he describes leaves no possibility for a gap to open up between them; it leaves no room for any questions that arise – it simply is. The reader may be unconvinced that Hegel is able to think “pure being”, and they would not be alone, as many of his fellow philosophers thought it was mad to try. All the other German Idealist’s had some form of starting point, such as Fichte’s “self-positing I” or Schelling’s “nature”, and they saw Hegel’s assertion to be a step too far. However, Hegel saw himself as the only one to take Kant’s critique of reason to its logical conclusions. For Kant, our relations to objects can go two ways: intuition is that which gives being, immediacy and sensuousness – whereas thought is possibility, conceptual structure and conceivability. In Hegel’s system, this distinction collapses, because his is a work of intellectual intuition without an object. As Being is not an object, and is utterly indeterminate, the Logic becomes an ontology without an object. The reason it is an ontology, is that if you are radically self-critical about both thought and being, you are left with the same thing: indeterminacy. But this is also the reason as a work of metaphysics, it is radically different than other metaphysical ideas, because it is explicitly not there.

In the next section I will elaborate how Hegel follows a necessary logic from this empty indeterminate space of “pure being”.

Hegel’s Metaphysical (Non-)Bedrock:

Being, Nothing & Becoming

“If pure being is taken as the content of pure knowing, then the latter must stand back from its content, allowing it to have free play and not determining it further. Or again, if pure being is to be considered as the unity into which knowing has collapsed at the extreme point of its union with the object, then knowing itself has vanished in that unity, leaving behind no difference from the unity and hence nothing by which the latter could be determined… There is nothing to be intuited in it, if one can speak here of intuiting; or, it is only this pure intuiting itself.”

(Miller, § 132)

Thought contemplates thought with no presuppositions, which abstracts the thinker themselves so that they “stand back”; this strange self-referential loop causes thought to vanish into its own indeterminate being. Being, supposedly the smallest unit of existence possible, is so pure and lacking in any content that it also reveals itself as “in fact nothing, and neither more nor less than nothing.” (Giovanni, p.59) In our search for a metaphysical bedrock of existence, the purest form of Being itself, we have ended up with a void. This complete nullity, however, is able to be intuited by thought and therefore is paradoxically the purest form of Being possible. The recognition of its own thought creates a sense of Being, but the recognition shows it to be completely empty. This means that “pure nothing” vanishes into “pure Being” in the same instant, being mutually exclusive yet necessary for each other. This reflexive turning of “Being into Nothing into Being…” violates any supposed “Law of Non-Contradiction”, seemingly able to embody two opposites in one form. As Hegel says:

“[…]it is equally true that they are not undistinguished from each other, that, on the contrary, they are not the same, that they are absolutely distinct, and yet that they are unseparated and inseparable and that each immediately vanishes in its opposite. Their truth is therefore, this movement of the immediate vanishing of the one into the other: becoming, a movement in which both are distinguished, but by a difference which has equally immediately resolved itself.”

(Miller, § 134)

A recursive interrelation, or contradiction, between the element of “nothing” and “being” is then seen as the higher sublation termed “becoming”; this movement is what generates the rest of Hegel’s logic. It is an inherently unstable movement, both is and is not, an “unrest of simultaneous incompatibles.” (Giovanni, p.67) Hegel sees “becoming” as being incorporated in everything that exists, with every entity made of “coming-to-be” and “ceasing-to-be”.

It is clear why Hegel’s thought has been called “mystical” or “psychedelic” by some commentators: the absence of any determination and the repeated cycle of “pure knowing” recognising “pure being” as the equivalence of existence and void, is remarkably similar in description to the state of non-duality some practitioners of meditation testify to. We can see how this distillation of thought to its barest essentials has revealed an ontological dimension that did not exist before. This ontology though, unlike most metaphysical thought, lacks any truth value. The logical structure mirrors the Epimenides paradox (“this sentence is false”), with the inclusion of self-reference generating an indeterminacy, or more accurately, an undecidability.

In the next part of this essay, I will explain how the distillation of human thought processes led to the computability theory, and its possible ontological implications.

How Turing produced computability from human thought

For any proposition like “the moon is made of cheese” or “X equals Y”, it is understood that for the claim to be true, there should be sufficient proof. In mathematics, proofs are arguments that substantiate themselves in their logical process, free from ambiguity or inter-subjective disagreement. One begins with a set of premises, also known as axioms, and these logically infer a sequence that results in a conclusion, called a theorem. If one agrees with the axioms and the steps the proof takes, then the theorem can be taken as “true”. In the past, before the creation of formal axiomatic systems, proofs were written in natural language, ad hoc notation and without justification of crucial steps. For rigorous truths, formal language with syntax was needed for everyone to be on the same page. There were many systems, with their own allowed rules of inference and starting axioms, but some became more foundational than others. First-order logic for instance, captured logically sound reasoning and is used in many philosophical arguments. For mathematics, nine “Peano axioms” were created to provide a foundation for natural numbers, while “Peano arithmetic” replicated human operations like addition and multiplication, which previously lacked rigorous definitions. These formal systems meant that every step of an argument could be truth-preserving, and lent logical necessity to final theorems; once discovered in a coherent language, a theorem can be replicated by the mechanical application of the rules that everyone agrees on. This mechanical nature of systems meant that mathematicians such as Leibniz dreamed of a device that could explore all the possible implications of a defined language, and given a possible theorem as input, determine whether there was a path to it. This procedure of following a finite sequence of instructions towards an outcome is termed an “algorithm”.

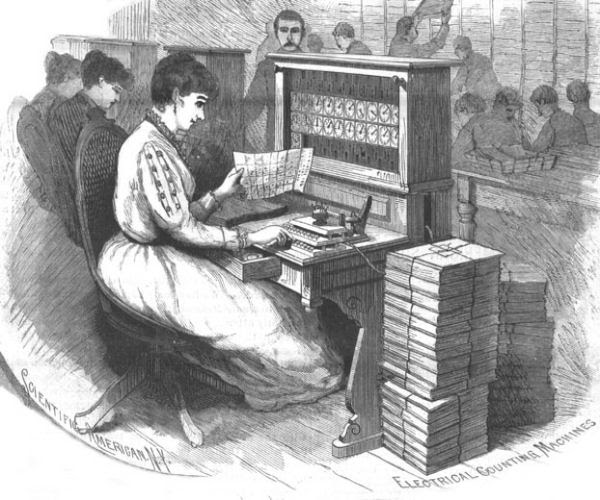

The Entscheidungsproblem, or the Decision Problem, was a challenge set out by David Hilbert and Wilhelm Ackermann in 1928. At this point, nobody knew what the basic elements of an algorithm were, apart from that they involved a sequence of instructions based on rules. The Decision Problem asks whether there exists a general method or algorithm that can be applied to any mathematical statement, and determine whether it is true or false. Thus, to find out whether the Decision Problem held, there needed to be a definition common to all algorithms, which arrived when Alan Turing abstracted human computing into its logical essence. (I will ignore Church, Rosser and Post’s contributions for expediency.) It should be emphasised that Turing sought his insights not from solely mechanical means or from examining mathematics. As he said:

“The real question at issue is ‘What are the possible processes which can be carried out [by a human] in computing a number?’”

(Robič, p.330)

In 1936 Turing published his paper: “On Computable Numbers with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem”, which aimed to distil human computation to its minimum intelligibility. Turing observed how humans engaged in calculation (who at that time bore the moniker “computer”), and saw a general process occurring: they would think and write down an integer, which they would read and then think some more, then would write a new integer. This would continue in a cycle until a final result. Turing’s insight was to abstract this process into its essence. He envisioned the paper that people used as a tape, split equally into cells containing either a blank space, a one, or a zero. This tape was theoretically infinitely long, so you can have as many intermediate steps deemed necessary. This mechanism would read one cell at a time, and was given the ability to change the cell; this would then move the tape left or right to a new cell, until it halted on the final computation. The halting would be the decision whether the algorithm, with a given system, was true or false. The machine had a finite memory, a lookup table, which specified the action to be taken given combinations of the possible states of the cell. Thus the lookup table governed its activity, which created an infinity of different possible “computing machines”, or “Turing machines”. A crucial discovery was that Turing machines could be encoded on the tape, so they could take as input other Turing machines. These were called Universal Turing Machines, because they could simulate and behave just like any other Turing Machine. These automatic algorithmic machines were later merged with electronic advances, creating the computers that exist today. Turing’s great achievement was finding a universal method of automating human mathematical thought by giving a concrete definition of what algorithms are and how to manipulate them. This definition of computability therefore also defines what it means for something to be non-computable: it would be a problem for which there is no algorithm that can be used to solve it.

Uncomputability & the Halting Problem

Gödel’s discovery of the Incompleteness Theorems proved that for any consistent formal system, there are undecidable propositions contained within it, which ensures that the consistency of a system cannot be proved within itself. A higher perspective is needed, from outside a given system, to prove its consistency. To figure out if there were uncomputable algorithms, Turing was inspired by the use of self-reference in the Gödel Theorems to generate logical contradictions within a formal system. In his 1936 paper, Turing discovered the Halting Problem, which proved that no Turing machine could solve all inputs, giving way to the general concept of computational undecidability. I will now give a simplified version of Turing’s paper.

The Halting Problem imagined a machine (here termed a “solver”) that could take as input two things: a description of a Turing Machine, and a corresponding input for the machine to solve. The solver analyses the input, and determines whether the given machine will halt on its algorithm. Turing then defined a second Turing machine, (termed a “contradictor”), that contains the solver as a submachine within itself, with some additional rules. The contradictor views the result of the solver, and performs an opposite action based on it. This will be either:

– Result:

Yes, the original machine will halt on its input.

Therefore: Enter an infinite loop, and prevent halting.

or

– Result:

No, the original machine will not halt.

Therefore: Halt the process.

Turing then encoded the contradictor machine on a tape, and then fed it to itself, thereby analysing its own behaviour. This means that if the contradictor halted, it would analyse this and will not halt, and vice versa; therefore, the same machine will behave differently on the same input, despite this being a clear logical contradiction. He originally assumed that a solver machine could exist that solves a halting problem for any other machine, which would be a contradictor machine; with this proof however, he proved that a solver machine cannot exist. Therefore, no Turing machine can solve the Halting Problem, and so it is an uncomputable algorithm. There are special cases where a machine could solve it for a finite set of other machines, but no Turing machine can solve all cases because they themselves will not halt on some inputs.

This discovery created a new possible answer for a computer. A computable problem will always output a yes or no answer, whereas an uncomputable problem outputs a third value: undecidable. There are many other undecidable problems, across computing and in number theory, with these impossibility proofs having far reaching implications. We can always partially solve undecidable problems by finding algorithms to solve special cases, but we will never yield truly general solutions for all of mathematics. In the next section, I will discuss the theory that if Turing machines do capture human computation, and therefore every conceivable algorithm that we can construct, then the ability of human computation and Turing computation have the real possibility of being identical.

The Church-Turing Thesis

The Church-Turing thesis, also known as the Computability thesis, came from analysing the differences between Turing’s method and others who had formulated definitions of computability. It was discovered that there was a remarkable applicability to Turing’s method: despite vastly different mechanical specifications of other systems, all of them were computationally equivalent to Turing machines, and vice versa. Turing’s close model of human computation and his more rigorous proofs meant that his model became canonical, but it could have been any other formulation; this means that underneath this variety of computational models, there exists a single phenomenon called computation.

The Church-Turing Thesis (CTT)

– A function of positive integers is “computable” iff it is Turing-computable (or λ-definable).

(Robič, p.322)

*iff = shorthand for “if and only if”

It has been disputed in the past whether the Church-Turing thesis is provable once and for all, but there is gaining acceptance of its real validity. There are numerous justifications, but I will highlight the most pertinent to this essay. For one, the CTT has never been refuted by showing a “computable” function that is not Turing-computable; therefore, we can look at computability theory and see that instances of the phrase “computable” are synonymous with “Turing-computable.” The previously mentioned equivalence of computational models to Turing’s definition is also a major clue that computability defined in this way is a general feature. Relevant to this discussion, Turing himself gave reasons to think that any humanly computable function is Turing-computable, by giving five general constraints to human computation that match his definition of computability:

“(i) Human behaviour is at any moment determined by his current “state of mind” and the currently observed symbols.

(ii) There is a bound on the number of squares which a human can observe at one moment.

(iii) There is a bound on the distance between the newly observed squares and the immediately previously observed squares.

(iv) In a simple operation, a human alters at most one symbol.

(v) Only finitely many human “states of mind” need to be taken into account. Then Turing’s analysis demonstrates that if a human “computation” is subject to these five reasonable and natural constraints, then it can be simulated by a Turing machine, a finite machine that operates in a purely mechanical manner.”

(Robič, p.340)

Turing also gave a “Provability Theorem”:

Every formula provable in the First-Order Logic L can be proved by the universal Turing machine.

This allowed the philosopher and logician Kripke to recreate the CTT in First Order Logic as a “special form of deduction”. Considering this, we can understand why the philosopher B. Jack Copeland has said:

“Essentially, the Church-Turing Thesis says that no human computer, or machine that mimics a human computer, can out-compute the universal Turing machine.”

(Robič, p.340-41)

It is clear that distilling human mathematical cognition down to its bare essentials has created the possibility of a seemingly universal mathematical and logical system of computation. In the next section, I will briefly show how this has led to theories of its ontological significance.

The Church-Turing Barrier

Due to these discussed factors, there is the real possibility of computing having a fundamental place in the physical universe. There are now versions of the CTT contending with this possibility; some generalise it for all algorithms, while others generalise it for complexity theory. The version with most relevance to the ontological question is the Physical CTT, which asks: “what can be computed by physical systems in general?”

The term “physical Church-Turing” thesis is often used, but the original thesis is also entirely “physical”; this term implies “non-physical” things, begging the question. For this reason, I use the term “computability thesis”.

In 1985, the computer scientists and physicists Stephen Wolfram and David Deutsch independently proposed a thesis, now defined as:

The Church-Turing-Deutsch-Wolfram Thesis (CTDW)

– Every finite physical system can be simulated to any specified degree of accuracy by a universal Turing machine.

(Robič, p.349)

The term “simulation” does not imply perfect accuracy, due to computers being discrete systems; this would mean classical continuous systems would disprove the thesis, as these involve uncomputable real numbers. This led to several other versions of the CTT in the literature, which after classifications and constraints, eventually led to a revised and more modest thesis by Copeland and Shagrir:

CTT-P-C:

– Every function computed by any physical computing system is Turing-computable.

(Robič, p.352)

This means that if a function’s values can be computed by physical processes of some physical system, then it can be Turing-computable. Therefore, if a function is not Turing-computable, then neither is it computable by physical systems. If the Halting Problem is undecidable, then if CTT-P-C is true, no physical system will be able to compute it. This sets a real physical upper bound on what is computable in this universe, now commonly referred to as the Church-Turing Barrier. Attempts to conceive physical computing systems that breach this barrier rely on having infinite computational steps in a finite span of time: these would be called hypercomputers, and if created, would falsify CTT-P-C. These proposals rely on some unfeasible methods; the most realistic example advocates using a computer situated next to a black hole to bend time. It is not clear whether this would be worth the effort.

If we take CTT-P-C to be true, this leads us to the conclusion that what humans can possibly compute, and what Turing machines can possibly compute, may be identical. This also means that non-computable problems set a limit, a “Turing Barrier” to the universe: this more general “computability thesis” cannot be proved, but only refuted by the discovery of “Super-Turing” reasoning that solves undecidable questions.

In the next section I will discuss the themes linking both Hegel and computability theory.

Strange Loops:

The Instability of Hegel’s Logic and Computability

Kant’s categorical judgements and Hegel’s derivation of “pure being” both see logical structure as central to thought, and I do not think it is trivial that computational theories express this, albeit in a different way. As I have shown, computing derives its logical operations from human thought, and further complexifies these operations organically through application in formal logical systems. This is not the end of the story though; I will now explain the theme of self-recursion in this essay, and its ultimate importance.

Douglas R. Hofstadter, in his book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, has a story that illustrates Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorems.

Imagine you have a record player named Record Player 1, that comes with a specific song named:

“I Cannot Be Played on Record Player 1”.

Out of curiosity, you decide to play it anyway. Unfortunately, this causes the record player to vibrate violently, and both it and the record breaks into pieces through pure sonic abrasion. You then go out and buy a new record player, with Record Player 2 written on the box. This also comes with a new song, named: “I Cannot Be Played on Record Player 2”. Again, your curiosity gets the better of you, and the same event occurs. You realise that for any Record Player X, there will be a song X that it is vulnerable to, thus ensuring the non-existence of a hypothetical Perfect Record Player.

Hofstadter then describes the creation of a Record Player Ω, which can analyse a record about to be played on it; if a dangerous song is presented, the Record Player automatically changes its own structure to remain a step ahead. Hofstadter places his theory of consciousness and identity in this concept, and while this line of thought is compelling, I cannot comment on its feasibility. What I find remarkable about his book, which is primarily concerned with computing, are the repeated unintentional similarities to Hegel’s system of thought (there is not one mention!). The logic of self-reference, the non-existence of the self, and the Epimenides paradox all make appearances; it feels as if Hegel had anticipated the computational paradigm of the 20th century before anyone else.

I agree with Hofstadter that self-reference ensures the incompleteness of any system: any bounded set is always unstable, always has its boundaries broken, when subjected to the right form of self-reference. This is reflected in Cantor’s infinite universe of sets, which is generated by the inherent instability of every set within it. Hegel’s Logic similarly shows how the collapse of the Identity of Thought and Being generates an instability that cannot exist on its own: “sheer indeterminacy of being” as utter instability. The sublation of Being and Nothing, their contradiction seen as a movement, ensures higher and higher forms of self-reflecting existence. Each side of the contradiction becomes more determinate and complex, but the central (non-)division remains.

“[Hegel’s Logic shows how] … Being will mutate logically into reality, being-something, actuality, and ultimately, space, whereas nothing, or the simple “not,” will mutate into negation, otherness, negativity, and ultimately, time. In each one, however, being and nothing as such will be preserved.

“Nowhere in heaven or on earth,” Hegel writes, “is there anything which does not contain within itself both being and nothing” (SL 85/1: 86).

(Houlgate, p.266-7)

To conclude, consider:

1 / 0

Bibliography

Special thanks to Ian Wright, who was very nice and took the time to respond to my emails and lend feedback. Here is the work of his that was the primary driver behind the creation of this essay:

– Di Giovanni, G., 2010. Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic. Cambridge University Press

– Hegel, G.W.F., 1991. The Encyclopaedia Logic, with the Zus tze: Part I of the Encyclopaedia of Philosophical Sciences with the Zusätze (Vol. 1). Hackett Publishing.,

– Hofstadter, D.R. (2000) Godel, Escher, Bach: An eternal golden braid. London: Penguin.

– Houlgate, S., 2006. The opening of Hegel’s logic: from being to infinity. Purdue University Press.

– Miller, A.V., 1999 George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic, Humanity Books

For references in this format: § ___, see:

Index to the Science of Logic (Miller). Available at: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/hegel/hl_index.htm.

Robič, B., 2020. The foundations of computability theory. Berlin: Springer.

Turing, A.M., 1936. On computable numbers, with an application to the Entscheidungsproblem. J. of Math, 58(345-363), p.5.

Leave a comment